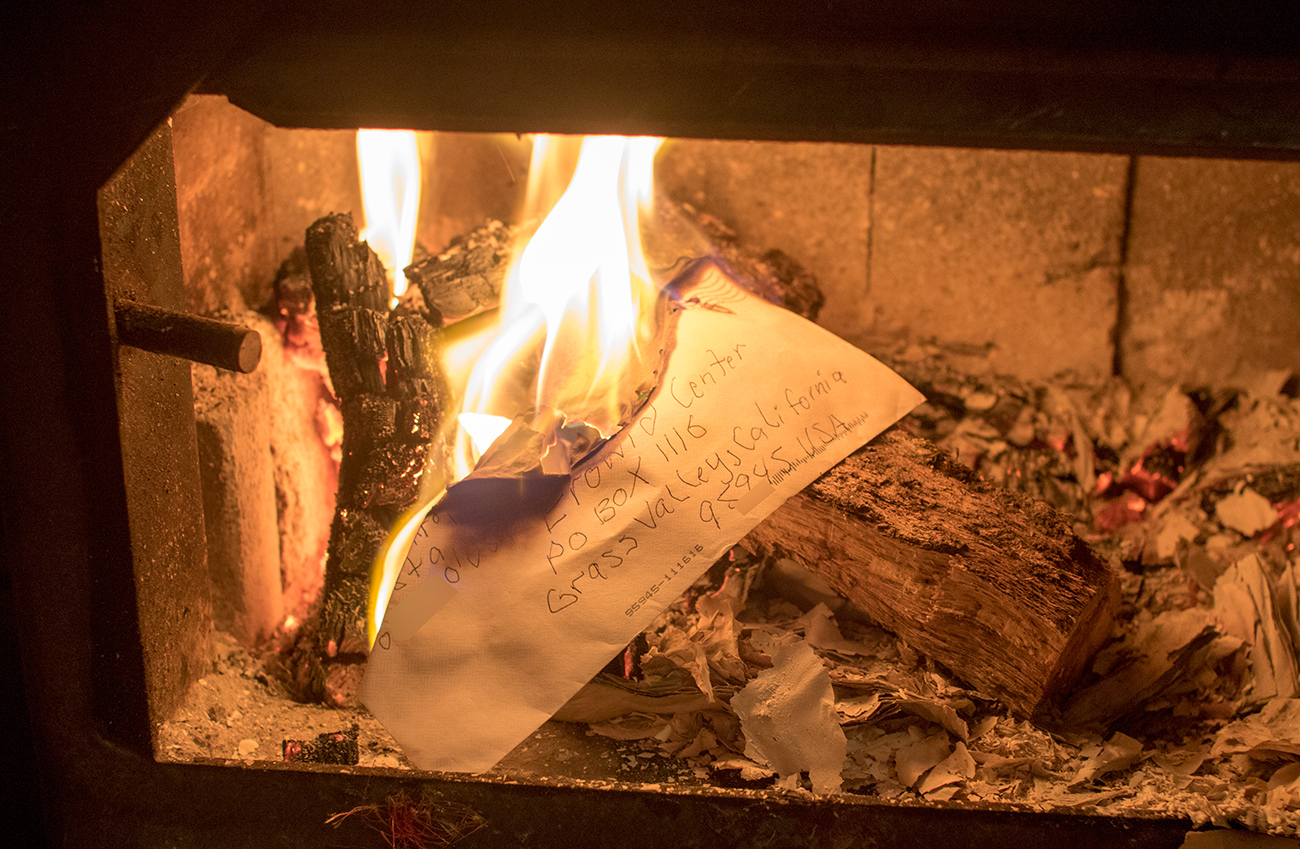

During the January 2018 Miracle (bloggy pre-description), it’s been hard to keep up with writing. Fire’s been posting to Facebook, but we have a bunch of photos and stories that haven’t been drafted yet. As we moved from the old library to the new, it was time to take the backlog of privacy-sensitive materials that are ready to be trashed, and do some destruction. We thought some people might enjoy seeing two of the ways we protect the privacy of submitters, correspondents, and donors.

Since we began Erowid, we’ve had the policy that we burn all paper with personally identifying information on it (envelopes, letters, donation slips) and when hard drives are retired out of our systems, they are not only data-wiped, but physically destroyed as well.

While a lot of people these days choose not to manage physical data drives, we have a complicated data delivery configuration that requires around eight physically separated drives to manage the development side of our published, in process, and unpublished data. Part of the need for so many drives is reliability of backups. Drives can be easily mirrored, and then the ‘hot’, the cold, and the backup drives can be easily swapped between secure locations.

We deliberately choose our systems based on lowest cost, highest reliability, and the requirement that no other agency or corporation can interfere with or index all of our back-end, development, and privacy-sensitive data. The Cloud is not an appropriate place or method for storing information that challenges societal norms; contradicts the putatively factual basis of criminal laws; and could possibly be banned in many parts of the world. So, our poly-hard-drive-requiring but high reliability data system does wind up with several hard drives per year that need to be retired with no possibility of data recovery.

Paper Incineration Policy

The “incineration policy” might seem a bit overboard except that we have lived in wood stove-heated houses for 22 years. So if we have to light a wood stove every winter day anyway, it’s easy to combine the two tasks.

Once the unit is up to a 12″ flue temperature of 400F (204C), the stove interior is insanely hot, up in the 900+ F range (500+ C). At this point, the blasting inferno is able to consume privacy-sensitive paper materials and turn them into a fine powdery ash.

It’s technically (and theoretically) challenging to recover any identifiable personal information from this ash. You might need to change Planck’s constant or the vector of time or something. Practically, our wood stove ash gets mixed with used cat litter and buried in our on-site waste midden.

A properly installed modern wood stove is ridiculously safe as long as you don’t put flammable things on them. (Like cats. No cats on the wood stove. It’s a rule. We use steel hard cloth to keep the cats from liking the horizontal space.) These stoves have fire-bricked interiors, engineered air flows, and double steel exterior walls with air gaps designed to cool the room-facing surfaces. But the top still gets crazy hot.

But, let’s move on…

Retired Data Drive Destruction

Stuff left over on people’s hard drives includes email addresses, names, credit card numbers, and other data and metadata that could be aggregated over time to create larger commercial value. For this reason, our policy is to destroy drives with private data instead of using simpler disposal methods, like shredding (a norm in the corporate world). We love Erowid’s supporters and we don’t want to endanger them or their privacy in unexpected ways. The process of destruction has a couple of perks.

First, it’s actually fun to destroy hard drives. As we move to solid-state drives (SSD) for storage, with all their efficiency improvements, it will be easier and less fun. Second, it yields magnets and weird e-waste beauty. This will get less beautiful as we transition to SSD.

It is really pleasurable to use perfectly suited tools* to dismantle the spinning platter drive boxes and then rip apart the internals and smash them with a hammer. It’s a bit like being a barbarian coming upon micro-technology for the first time. “How the hell do they wind that copper that thin and that tight? Oh my goodness! How strong these magnets are! Aliens, I tell you in all seriousness.”

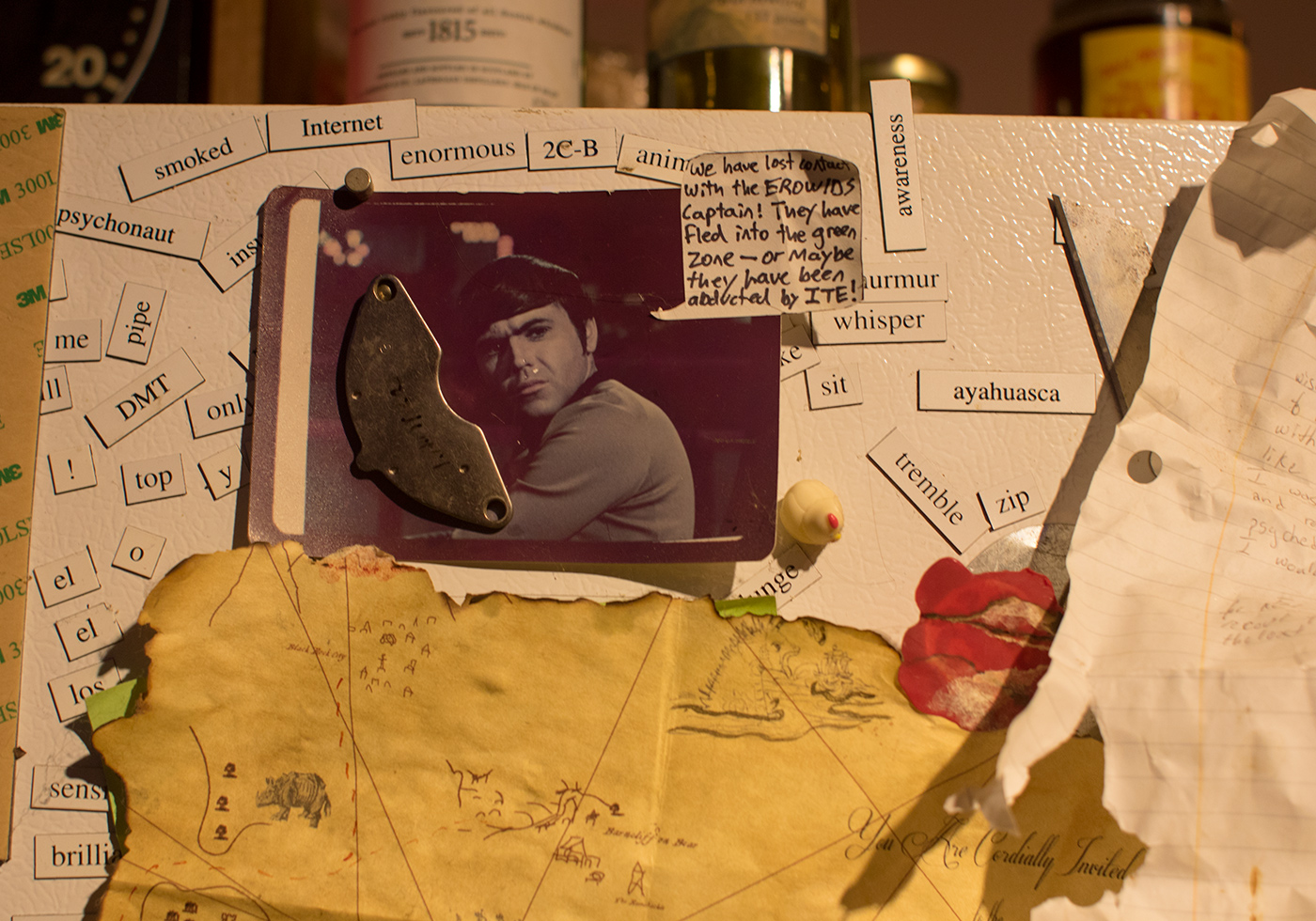

The shape of the coil evokes alien involvement in civilization, and Burning Man<tm>. You would never see the connection unless you had the right screw driver, a hammer, and cannabis-enhanced associative ideation.

There are a number of different types of internal platters, some are more like bendy metal and others are more like glass. But all of the spinning-platter hard drives from the last 20 years have really strong magnets in them. So, we have a collection of strong magnets taken out of all the drives Erowid has had. They cover the fridge, they sit in little clumps that are slightly dangerous to take apart.

Method:

1) Put drive on table.

2) Get out pleasantly geeky screw driver collection, purchased every 10-15 years, like the *I-FixIt tool wrap:

3) Find the right screw driver and it’s physically pleasant to open the steel cases to expose the drive platters, chips, and read heads.

4) Put the now opened drive in a large Rubbermaid tub.

5) Put on safety goggles.

6) Smash as hard as you can with a good-sized hammer. Hit it over and over and over until your arm is super tired. Take a breath and use your other hand.

7) Enjoy the weird visual and physical world you’re interacting with. Holy cow, I live during the transition between stainless steel and nano-tech. Zowie.

8) Smash it again. It’s ok to feel a little anger here. It’s better to think of it as a release of stored up energy. I’m not angry, I just need to get the “SMASH” energy up enough to hammer destroy.

9) Hold the pieces up to the light and check em out. Grab pliers and yank out other parts. Examine closely.

9.5) Enjoy the reflections from the broken mirrored parts. Visionary (de)Synthesis!

10) Did I mention gloves? Once you encounter glass platters, you probably should have been wearing at least one glove.

In the next photo, note the glass shards of the platter. Note the drive head arm. Note one of the two magnets visible in the bottom left corner. The top magnets are rarely, if ever, secured with screws and are very easy to get out. Usually the second magnet requires a different driver to release the reader head arm control coil (the alien Burning Man head above), then liberating the bottom magnet often requires the removal of one or two screws.

Through the destruction process, we’ve collected a lot of very powerful magnets and turned them into fridge magnets, tarp-hold downs, etc. A 15-year-old hard drive magnet firmly supports Mr. Chekov in his charming, country-boy valiancy.

Most of these magnets are attached to ‘legs’ (aka a bracket) that you can leave on them to create an air gap between the magnet and fridge, making them much easier to move around. Super duper fun.