Once upon a time there were hippies in Orange County, California.

To someone like myself who has lived in this ostensibly conservative region for some time, this might already seem like a fairytale. How much more so then to realize that these OC hippies worshipped LSD as a sacrament, distributed unbelievably massive quantities of it, pioneered smuggling hash out of Afghanistan while forming an enormous hash and weed distribution business, counted Timothy Leary as one of their own for a few years and bankrolled his prison breakout by the Weathermen, and were eventually prosecuted out of business by Orange County cops?

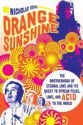

The “hippie mafia” in question was the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and the latest (and by my count only the second) major book to tell their story is Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World by OC Weekly investigative reporter Nick Schou. This non-fiction account reads like a late 60s crime thriller, though the crimes in question seem mainly to be quenching an enormous thirst for weed, hash and acid among the young recreational drug-using subcultures of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Though true, it is an amazing tale, especially in Schou’s telling. Schou gets this scene, the humor of it, the foibles, and the sheer legendary stonedness. He also stresses the anecdotal and personal over the larger context, unlike an earlier account of the Brotherhood by Tendler and May. That book, engaging and informative, focused more broadly on LSD in both its cultural milieu and also its main manufacturers. Orange Sunshine focuses almost exclusively on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love itself, with a major exploration of their hash smuggling exploits. Thus the title is a bit of a misnomer.

The Brotherhood was initially a group of violent thugs from the flatlands of Orange County and LA, some of whom were also surfers, who got religion in the form of LSD. Utopian in orientation but street dealers in practice, they figured out how to make a bunch of money from smuggling and distributing their favorite drugs. They didn’t, apparently, ever quite learn how to not bring their work home with them and the tale of their success and dissolution almost seems to suggest that smuggling drugs was the easy part, while just existing while being on so many drugs all the time was tougher. Eventually, carelessness, misadventure, bad luck, and snitches put an end to the Brotherhood. The LSD manufacturing and hash smuggling continued, but that’s another story.

Orange Sunshine mixes together great huge swaths of seemingly disparate Southern California culture. Mean flatland thugs, crazed canyon bikers, stoned coastal surfers, pan-Californian acidheads: the Brotherhood is where these subcultural strands came together. Always seeking a utopian escape, some of its members fled to Maui, where these transplanted pot smugglers turned to big-wave surfing, created Maui Waui, and appeared in the film Rainbow Bridge with Jimi Hendrix, whom they dosed with a DMT-laced joint during his performance. In the great tradition of the Southern Cal/Northern Cal rivalry, the Brotherhood seems simultaneously more heroic, hedonistic, and moronic than the Haight crowd, whom they happily sold weed to and bought Owsley acid from. One of their few NorCal appearances was showing up to dose the Hell’s Angels with acid at Altamont. Sadly, the Brotherhood seemed to have no “house band” counterpart like the Bay Area’s Grateful Dead (one hesitates to guess what this would have sounded like), but its members did include the former drummer of Dick Dale and the Del-Tones. (Dale, the most influential guitarist in the history of surf music, was based in Orange County.)

Schou has a great, almost pulp-entertainment way of telling this story and seems to have put in abundant time interviewing participants of the scene, and the larger-than-life characters he describes come bursting off the page. Most notable is John Griggs, a mean son-of-a-bitch 50s-style jock who changed dramatically after sampling LSD stolen at gunpoint from a Hollywood producer. He became a sort of LSD visionary, leading the Brothers from their criminal ways to, well, way more stoned and peaceful but still criminal ways. Eventually he decided to drop out and formed a communal ranch group in the mountains near Idyllwild, California. It was here that he tragically died of what was reported by onlookers to be an overdose of “synthetic psilocybin” (see Afterword). This sort of horrible comeuppance seemed to be the fate of more than a few of the elite members of the Brotherhood, with accidental deaths, overdoses (including those of children), and busts far too common, though few of the Brotherhood ever served serious time.

But this is not really a cautionary tale, it’s an adventure story, and a ripping one at that. The moral of the story, if there is one, is “Wow, it sure would have been fun to live in Laguna Beach in the 60s!”* It nicely complements other accounts of the cultural history of acid in the 60s such as Storming Heaven and Acid Dreams. Read those for the insightful discussions of the major political shifts and cultural changes of that singular and incredible era, as well as for the equally incredible story of the CIA’s engagement with acid. But read Orange Sunshine for the kicks.

*Actually I did live in Laguna Beach from ‘66 to ‘67, but I was two years old and my parents moved our family, in part, to get away from the drugged-out hippies.

Afterword:

Unfortunately, I find it necessary to write an afterword, as this book is attracting some controversy from within the psychedelic community. The main charge is that the book is error-ridden and inaccurate, the reason being that key participants were not interviewed and some of those who were may have had their own vested interests in providing misleading information. Nick Schou has told me that he made every effort to interview key protagonists including, for example, Nick Sand, who declined several interview requests. Others who denied requests remain anonymous. At the same time, I feel it necessary to point out that Schou did interview a lot of former members of the Brotherhood as well as their family or other hangers-on, thus while it is certainly possible that the book contains some errors, distortions, or omissions, it is impossible to dismiss it as being poorly researched. It clearly and obviously isn’t.

A couple of issues remain. First, there are questions about whether John Griggs really died of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin. I’ve asked Schou and he replied:

“Yes this question always comes up every time someone mentions Griggs’ death. Although it’s not in the book since I only talked to [Brenice] Brennie Smith after I turned in the manuscript, he was there the night Griggs died and confirms that he died of a toxic reaction to a crystallized form of psilocybin as stated in my book. Who knows what else was mixed in with it, but by all accounts, it was poisonous in the extreme in so far as Griggs ingested far too much of it, according to Smith as well as other Brotherhood members who weren’t there but got that story straight from those who were present. Nobody I interviewed for the book who was in the Brotherhood and on the scene when he died have any confusion that this is how he died. It was widely known among the Brotherhood that this psilocybin was making the rounds, see where I mention Ed Padilla mentioning Griggs’ enthusiasm for the stuff the last time he saw Griggs. Some speculate that Griggs choked on his own vomit on the way to the hospital, but Smith says this is not the case and backs up the version in my book.”

Schou also enclosed a death certificate, which listed Griggs’ death as a consequence of “suspected drug intoxication (psilocin)”. This is one of the few known deaths claimed to be caused by an overdose of psilocybin/psilocin. Given that no other fatal ODs from synthetic psilocybin or psilocin have ever been reported, it is possible that this was actually something else, or that the psilocybin was contaminated or adulterated.

Another question is more serious. In October 2009, Schou wrote a story for the OC Weekly on former Brotherhood member Brennie Smith, who had arrived in California in part to be interviewed for a documentary on the Brotherhood, and was arrested on an outstanding warrant.1 Apparently there is suspicion in some quarters that Schou’s publicity of the Brotherhood from his prior OC Weekly stories on the group led to law enforcement’s previously dormant interest in Smith, or that Smith arrived at Schou’s behest. Schou insists that he had no knowledge of Smith’s visit until he arrived, and in fact he gathered information helpful to Smith and shared it with Smith’s defense attorney. Schou’s stance on the ludicrousness of arresting and charging Smith is evident in the follow-up he penned later in October 2009.2 Given Schou’s record of articles and investigative news reporting critical of the War on Drugs and the generally critical bent of the OC Weekly on Orange County law enforcement, the allegation that Schou somehow contributed to Smith’s arrest seems baseless.

Clearly, those who were there and participated are in the best position to evaluate Orange Sunshine’s accuracy, but given the complexity of the Brotherhood, its changes over time, the number of now elderly interviewees Schou talked to, and the fluid nature of memory, this is probably about the best account of a bunch of drug smugglers from 40 years ago that we’re likely to get.

——1) Schou N. “Was Brotherhood Member Brenice Lee Smith a Felonious Monk?“. OC Weekly. Oct 22, 2009.

2) Schou N. “Why is Brenice Lee Smith Still Behind Bars, Awaiting Trial?“. OC Weekly. Oct 28, 2009.

Fatal error: Uncaught TypeError: count(): Argument #1 ($value) must be of type Countable|array, null given in /www/library/review/review.php:699 Stack trace: #0 {main} thrown in /www/library/review/review.php on line 699