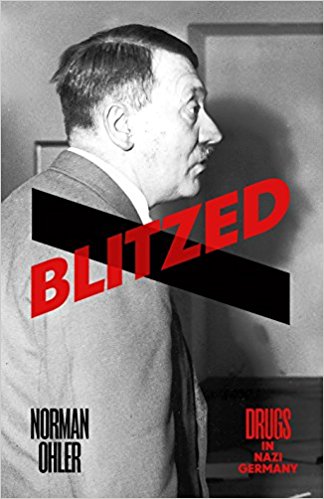

Stories of rampant drug use during World War II have long been rumored or discussed as quasi-secret history, but the extent to which these stories are true and what exact significance drugs had during the war are topics in need of detailed investigation. Blitzed examines the role that various drugs played in the Third Reich by telling three main stories: the popularization of methamphetamine pills under the name Pervitin and their widespread use by the Germany military and civilians; Hitler’s use of narcotics and other drugs during the war; and the story of Hitler’s personal doctor Theodor Morell and his unorthodox prescriptions for “Patient A”, or as Ohler dubs him, “High Hitler.” The book is the result of years of research in various official archives containing original documents including Morell’s own diaries. It is an engrossing, startling, and of course cautionary tale.

To set the stage, the Nazis emerged from drug-heavy Weimar Germany, where German pharmaceutical companies such as Merck dominated the global production of opiates and opioids, as well as cocaine. Morphine and cocaine were easily available in Berlin and other major Germany cities. The mood of social licentiousness we associate with the Weimar Republic—where prostitution involving children as well as adults was ubiquitous—was a contributing factor in the emergence and rise to power of the Nazi Party. Nazis condemned drug use and Weimar culture in general as degenerate, and preferred beer. Once in power, the Nazis enforced an early war on drugs, with accompanying propaganda that blamed Jews or foreigners for the social poison of drugs. The exception was methamphetamine, first synthesized in Japan and later mass-produced by the German pharmaceutical firm Temmler. Heavily marketed as a performance-enhancing drug, cure for withdrawal from other drugs, and general panacea, Pervitin was the one drug sanctioned by the Third Reich, and it was a huge hit with the German public. As a sign of how accepted it became, Ohler describes how chocolates were manufactured with huge doses of methamphetamine inside and when coffee supplies dwindled, Germans substituted Pervitin.

Ohler delves into how the mass production and dissemination of Pervitin to German soldiers was clearly an extremely important ingredient in the early military success of Germany’s Wermacht. The Panzer division invasion of Poland was fueled by meth, and the Blitzkreig strikes on Belgium, the Netherlands and France were made possible by German soldiers’ ability to advance quickly, day and night, without stopping, a result of Pervitin-induced wakefulness. The added confidence boost and feeling of euphoria clearly didn’t hurt morale. Ohler hints that even some of the generals who came up with the plan were consuming methamphetamine. The breakneck speed of German moves took the French and British off-guard and led to a stunning German victory, only somewhat marred by Hitler’s refusal to complete the rout by attacking the remaining British and French armies they had surrounded, most of whom were inexplicably allowed to escape through the hastily organized flotilla from Dunkirk.

On the Eastern front Pervitin also played a huge role, though eventually far less successfully. As Ohler points out, methamphetamine is effective for a while, but at a cost. A long, sustained military campaign cannot depend on stimulants, as the eventual stimulant crash requires a lengthy period of sleep and recovery, often leaving soldiers in a weakened and depressed state. Thus, while Pervitin may have aided early German victories, it couldn’t win them the war. In a sense, methamphetamine’s success in aiding the initial German attacks led directly to Hitler’s overconfidence and thus the military mistakes that ended up leading to defeat. The issue of German war crimes’ relationship with methamphetamine use is also discussed, but the evidence here is inconclusive.

A key figure in this narrative is Hitler’s doctor, Theodor Morell. Morell comes across as a deeply unethical bootlicker and quack who was nonetheless able to keep Hitler functioning through the war, though in an increasingly narcotized state. At the time he first met Morell, Hitler suffered from a variety of maladies, perhaps related to poor nutrition and his strict vegetarianism. He benefited substantially from Morell’s mysterious injections, which probably involved glucose, vitamins, probiotics, animal proteins, anabolic steroids, and hormones, and possibly stimulants or depressants. The unorthodox doctor swiftly became his personal physician. Despite meticulous research it is still not clear to what extent any of the many daily injections Hitler received during the early years in bunkers contained stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine (“a Jewish drug” according to Hitler). But by midpoint in the war, in his effort to keep der Fuhrer in a functional state, Morell had turned to adding the German-invented drug Eukodal (oxycodone) to the injections. As Hitler’s dependency and the war turned against Germany, Morell continued to administer oxycodone along with a strange and varied admixture of up to eighty ingredients. By the end it became clear that Hitler was essentially a junkie. In the meantime Morell, now Hitler’s key confidant, was trying to corner the market on injectable animal products, and scouring Germany for remaining stores of drugs. Morell and Hitler are intertwined figures in this account, each dependent on the other, both increasingly desperate as the hopelessness of the German military campaigns became clear.

Hitler was not alone, as other key Nazi figures such as Göring were also users of narcotics, and one imagines many also used Pervitin. Morell ended up giving treatments to such figures as Albert Speer, Heinrich Himmler, Benito Mussolini, Leni Riefenstahl, and many others.

Ohler denies that his book is trying to explain the entirety of Germany’s role in WWII or Hitler’s psychopathology as a product of drug use. Nonetheless, it is clear that he is making a case that many details of the war, from the initial German military offensive to Hitler’s increasingly poor decisions were indeed related to the use of drugs such as methamphetamine and oxycodone. His research and account are convincing. I think Ohler’s concern is that we not think of Hitler as somehow less culpable for his actions because of his drug use and eventual addiction, but few reading this account will come away with that impression. The drugs simply facilitated Hitler’s ability to continue pursuing his original deadly agenda. Nonetheless, criticism of this book has been widespread among American and European historians and journalists who bewilderingly conclude the account is “sympathetic to the Nazis”. Insofar as it tells a story about Nazis, that seems to me to be the sum of its “sympathies.” Perhaps if this book had been published at a time when there was less unfounded hysteria about Nazism’s resurgence it would have avoided these slanders. In any case, Blitzed is an amazing read.

Fatal error: Uncaught TypeError: count(): Argument #1 ($value) must be of type Countable|array, null given in /www/library/review/review.php:699 Stack trace: #0 {main} thrown in /www/library/review/review.php on line 699