Modern Psychedelic Art's Origins as a Product of Clinical Experimentation

v1.1 - Jun 13, 2013

Originally published Mar 2004 in The Entheogen Review

Citation: Stuart, R. "Modern Psychedelic Art's Origins as a Product of Clinical Experimentation". The Entheogen Review. 2004;13(1):12-22.

There is a common belief that hippies in the United States invented psychedelic art in the 1960s. Actually, modern psychedelic art began in Germany four decades before the "Summer of Love." This art first appeared in clinical settings, unaware of its antecedents in native societies and little influenced by earlier Western drug art from the 1800s (see Figure 1).

Subjects #3 and #31 were doctors who took 500 mg each, in different experiments. They both drew "trails" produced by the glowing end of a moving cigarette. Subject #31 looked at upholstery with a batik pattern of checks and squares. He then looked at a book, and the textile patterns transferred to the book and proceeded to metamorphose into the designs he represented in three drawings.

Subject #10 was a doctor who was administered 400 mg. He was inside a building looking up at light coming down through a domed concrete ceiling. Closing his eyes, he felt elevated into the dome and identified with it. "It was as if I was inside the cupula, and looking up as the light was going through. At the same time I had a sort of physical sensation of the entire construction, the ability to feel what this kind of iron/concrete construction was like from the inside." The subject drew a grating of iron slates with bronze ornaments that was part of the construction.

Subject #17 was a doctor who was given 400 mg. Looking at a rug, she commented, "The whole carpet seemed to me without sense." She drew a stylized crab, an animated form that she imagined in the carpet.

Subject #18 was a law student who took 400 mg. Either during or after his session, he illustrated the phosphenes that he produced by pressing on his closed eyes. He described, "With closed eyes there was again a strongly ordered surface of color changing like a kaleidoscope and taking on geometrical patterns that were crisscrossing as if lit up by a flashlight."

Subject #23 was a doctor who was administered 500 mg. He drew phosphenes to illustrate the following experience. "I closed my eyes and pressed on the eyeballs and saw small circling white points and later these apparitions transformed into kaleidoscope-like whirls of small red and green flecks of color like an ocean of little pennants. Red and green played from now on until later in the afternoon, and I see only red and green in the world and I am searching for blue and yellow." He also drew "eggdart-molding," which was an architectural molding with filigree ornamentation, that he imagined in the glowing band emanating from an electric lamp that was moving back and forth. The subject was shown a test pattern, designed by the Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer, to test for the perception of illusory movement and colors. The subject recounted: "the pinnacle or apex of the triangle moved from A to B and back. There were no colors, they were gray." The subject drew two sketches of the moving triangle.

Subject #26 was a doctor. He drew six pictures illustrating his experience with a 500 mg dose. He described what he imagined while looking open-eyed into a dark cellar. "From this black space emerged colorful swastika figures--innumerable, all of them around me, in front and back, above and below, right and left. I must have been in the middle of them. They were not actual swastika, but rather like this (indicating the drawing). And then began from the points of the hooks innumerable spirals and flashes and lines. The swastikas disappeared when the music turned on. Unusual, mostly red and green, geometrical figures appeared again in numerous places. This time they moved in pleasant rhythm, sometimes hastily, sometimes slowly, then taking on the most bizarre architectonic forms... The splendid color and rhythm melded into a certain harmony."

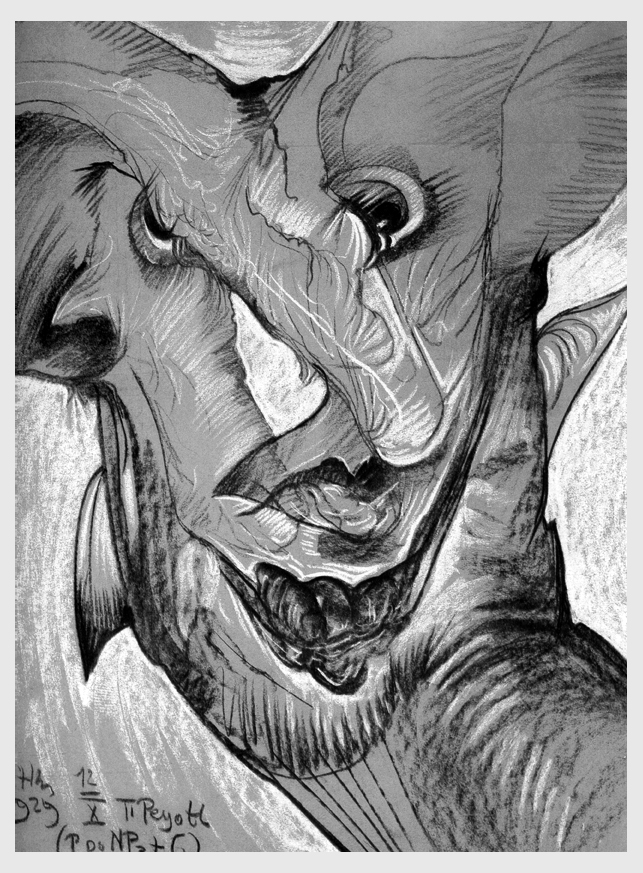

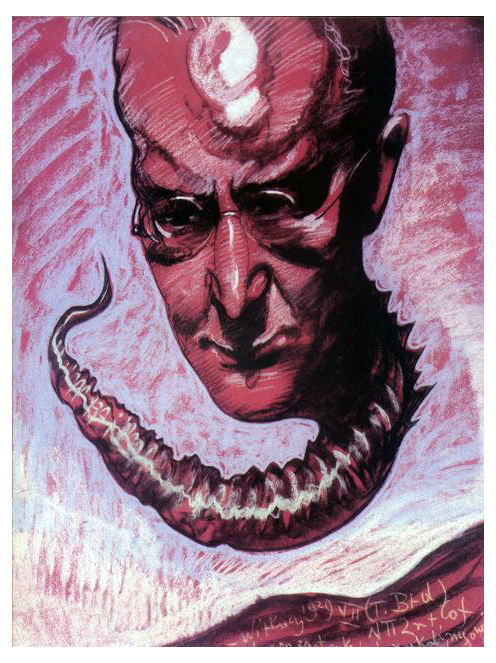

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (a.k.a. Witkacy) was a Polish philosopher, playwright, and artist. He obtained peyote from Warszawskim Towarzystwie Psycho-Fizycznym (the Warsaw Metaphysical Society), and later from the scientists Alexandre Rouhier and Kurt Beringer. He also got mescaline directly from Merck pharmaceuticals. An expurgated version of his description of a peyote experience was published in his 1932 essay Narcotics. The censored text originally included surreal sexual imagery such as "violet sperm-jet straight in the face, from a hydrant of mountain-genitals." Author Marcus Boon commented: "Profane and misanthropic, Witkiewicz's prose reads somewhat like a modernist version of Hunter S. Thompson's" (Boon 2002). Boon speculates that Witkacy's novel Insatiability may have been influenced by his peyote experiences. Apparently, Witkacy was the first modern artist to work under the influence of a classical hallucinogen. In 1928, Witkacy took "peyotl" under the supervision of Drs. Teodora Bialynickiego-Birula and Stefan Szuman. Dr. Szuman published illustrations of Witkacy's peyote and mescaline visions in 1930. In 1990, Irena Jakimowicz published a 1928 drawing and ten pastel portraits created from 1929 to 1930 that Witkacy made under the influence of peyote, as well as three drawings and five pastel portraits he made under the influence of mescaline (see two examples, Figures 2 & 3).

In 1932 Frederic Wertham and Manfred Bleuler administered mescaline to normal subjects to study visual hallucinations:

In 1933 G. Marinesco published a drawing of a hand seen under the influence of mescaline. The thumb was reduced to a pointed protrusion and the fingers were of inconsistent size.

In 1934 Dr. Fritz Fränkl, who was living in Paris after having fled the Nazis, injected a small dose of mescaline into his roommate, Walter Benjamin (Thompson 1997). Benjamin drew three pictures that consisted of words about sheep and witches poetically scribbled across the page. He also produced, while under the influence of Cannabis, a picture of a bird.

Walter Benjamin is currently an extremely popular philosopher, especially in literary circles. There are fourteen volumes of his work published in German, and five volumes of English translations published by Harvard University Press. One of the foremost experts on Benjamin is George Stiener. In Amsterdam, Stiener opened the 1997 Congress of the International Walter Benjamin Association by giving the keynote address. The assembled congregation of scholars visibly bristled as Stiener lectured about Benjamin's drug usage, which went back at least to 1927, possibly even earlier. Stiener said that the eleven extant drug protocols were only the "tip of the iceberg," because Benjamin had hundreds of sessions with hashish and other drugs. Stiener related these sessions to Benjamin's obsession with Baudelaire and his interest in the influence of dreams and hallucinations on art. Although Stiener emphasized that these experiments occurred before the legal prohibition, when societal attitudes were different than today, the audience was quite disturbed. The academic world fears that mentioning Benjamin's drug use would discredit the legitimacy of his ideas. For example, one contemporary Benjamin scholar--terrified that his career would be ruined if he seemed to encourage drug use--decries any public discussion of Benjamin's pharmacological explorations. Yet he has stated privately that he finds the topic interesting.

Only a few of the drug protocols that Benjamin participated in were published in English. There were a few hashish experiments scattered in the various volumes produced by Harvard, but no mention of Benjamin's use of mescaline. City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco agreed to publish Scott J. Thompson's English translation of Benjamin's collected drug protocols. However, Harvard University Press owned the copyrights, and Lindsey Waters, Executive Editor for the Humanities at Harvard University Press, told Thompson that he would not sell publication rights to City Lights, nor would Harvard be interested in publishing such a compilation. Waters said, "We are very interested in publishing translations of Benjamin's work, but we can not undermine Benjamin's reputation by making him appear to be a drug addict." It seems that Janus-faced scholars and bowdlerizing editors are suppressing academic discussion about legitimate scientific experiments! Incidentally, Benjamin's preoccupation with recurrent hallucinogenic ornamental motifs may have been influenced by parallel observations by scientists (Knauer 1913).

Drs. Eric Guttmann and Walter S. Maclay of Maudsley Hospital studied art produced by psychotic patients and by mescaline subjects. Art generated by their 1936 mescaline experiments is preserved in the Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives and Museum in Kent, England. Bethlem also has a collection of pictures by Richard Dadd and other artists who suffered mental disorders.

In his 1948 doctoral dissertation for the Medical Facility of the University of Heidelberg, Hans Friedrichs described a series of tests conducted from 1937-1938 at the Psychologischen Institut der Universität Bonn (Psychological Institute of the University of Bonn). The subject of the experiment was a 24-year-old student of philosophy and mathematics who spontaneously produced six drawings approximately eight hours after being injected with 300 mg of mescaline sulfate. These pictures represented the "extraordinary profusion of images powerfully charged, in part, with emotive associations so difficult to describe" that he experienced during the peak of the session. He wrote a statement about the last illustration, which he submitted along with his drawings to the test director:

Giuseppe Tonini and C. Montanari worked at the Ospedale Psichiatrico "L. Lolli" in Imola, Italy. In 1955 they administered drugs to an artist who worked in the hospital's occupational therapy department. The two researchers adhered to the psychotomimetic paradigm, and described their subject as a having a normal but "slightly primitive" mind. They asked the artist to paint during his sessions with mescaline, LSD, lysergic acid monoethylamide (LAE 32), as well as with methedrine (both alone and in combination with either mescaline or LSD). He produced paintings during all sessions except the one on LAE-32. The doctors published seven of his paintings of flowers in vases and a landscape, along with a comparison drawing by a schizophrenic. They concluded, "The pictures do not contain any new elements in the creative sense, but reflect psycho-pathological manifestations of the type observed in schizophrenia" (emphasis in the original; Tonini & Montanari 1955). The researchers believed the drawings expressed the differences in the mental states elicited by the different drugs. Although the pictures did look different from each other, it would not have been possible to pick out which picture was painted in an ordinary state of consciousness.

Four prominent American graphic artists were asked by Louis Berlin and his colleagues to paint under the influence of mescaline and LSD. Three subjects were disinclined to paint while peaking, preferring instead to "look and feel," while the remaining subject "painted with great fervor and excitement." Paintings done under the influence of a psychedelic were "works of greater esthetic value appeal according to the panel of fellow artists, but this was associated with a relaxation of control in the execution of lines and employment of color, so that both color and line were freer and bolder." The doctors explained:

During the "Draw-A-Person" test and Bender-Gestalt doodles, the artistic style was more bizarre, expansive, and free when the subject was under the influence. The drugs caused an "impairment of the highest integrative functions" as measured by other standardized psychological instruments. These were naïve subjects "unaccustomed to the use of 'drugs'," so perhaps their performance on "integrative functions" would have improved with practice.

Max Rinkle, M.D., initiated the United States' first LSD research in 1949. Rinkle (1955) reported that he and Clemens C. Benda, M.D., "gave mescaline and, on another occasion, LSD to a nationally-known contemporary painter who showed a progressive disintegration in his drawings though each line showed the superior craftsman in his art."

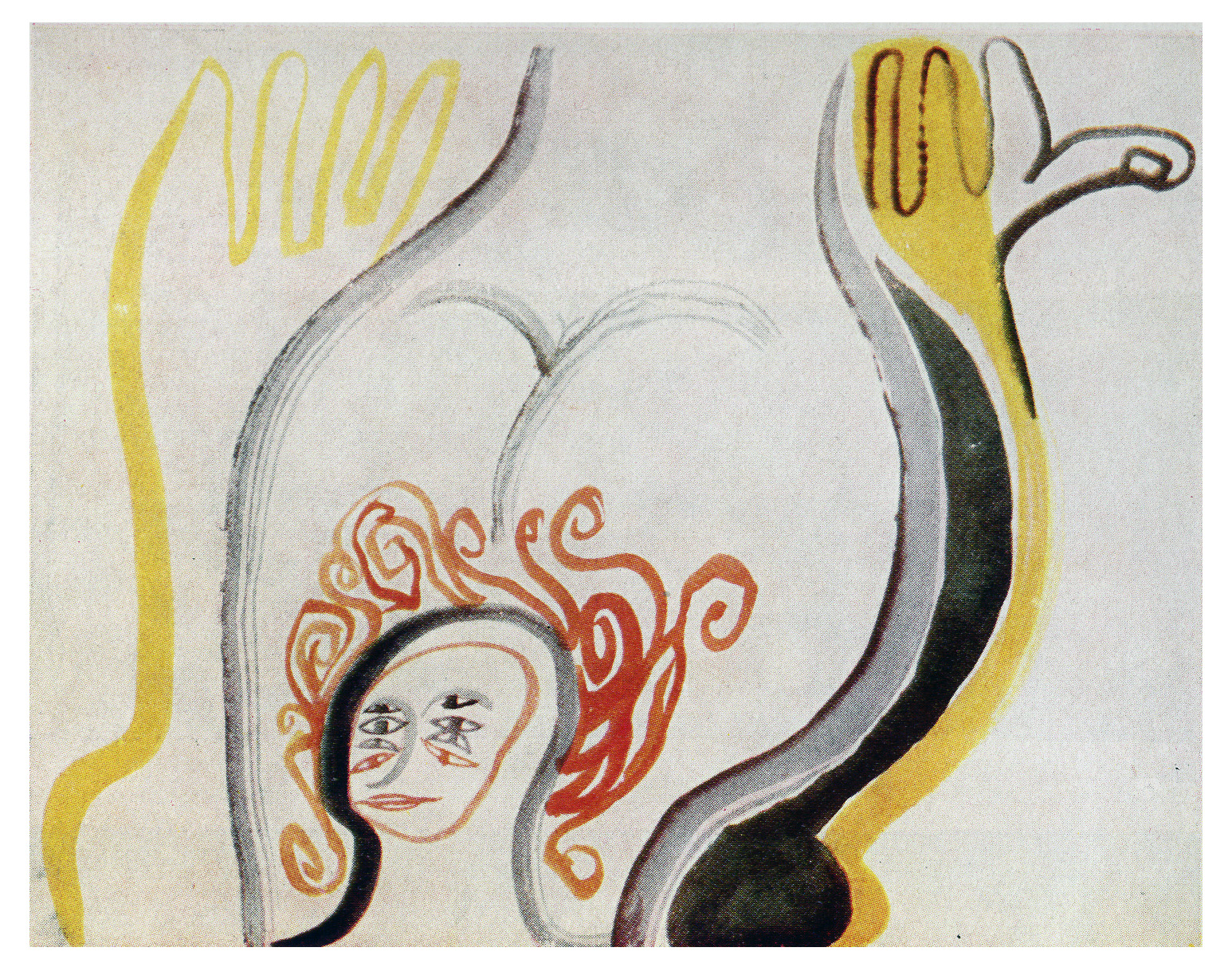

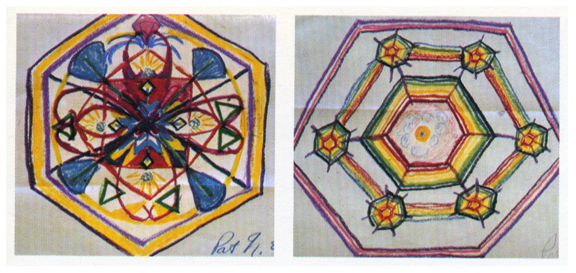

Dr. Jiří Roubíček's 1961 book Experimentální Psychosy (Experimental Psychoses) described research in Prague, providing numerous drawings and paintings, including 20 color plates (see Figures 4 & 5). These pictures were by subjects under the influence of psychedelics (some of whom were well-known professional painters), and by mental patients. Roubíček's book notes that between 1952 and 1960 at the Psychiatric Clinic of Charles University, Czechoslovakian psychiatrists conducted "11 experiments with mescaline on healthy subjects; 130 experiments with LSD on 76 healthy volunteers and 80 experiments on 44 patients; with psilocybin 8 experiments on healthy subjects and 7 on patients; furthermore occasional experiments with other drugs, tryptamine substances and benactizine." The text's English translation summary retains psychotomimetic terminology that characterizes psychedelics as "delirogens" that produce "toxic psychotic conditions." The art of healthy psychedelic subjects is described in comparison to schizophrenic art:

It was not surprising that hallucinogens came to the attention of creativity researchers who were already interested in dreams, eidetic imagery, hypnogogic imagery, and synesthesia (McKellar 1957). They considered these drugs as being useful for understanding abnormal thought processes. Around the same time, psychedelics also came to be regarded as tools for enhancing creativity or for art therapy. In 1955 J.J. Saurí and A.C. de Onorato gave LSD to "autistic schizophrenics," who made artistic images that expressed greater openness and readiness for interpersonal contact. Psycholytic therapist Hanscarl Leuner described psychotherapy wherein chronic neurotic students attempted to use art to portray the content of their hallucinations induced by LSD and psilocybin. Leuner said that three subjects initially produced stiff drawings, but after subsequent drug sessions they made "large-surfaced freely-conceptualized and often unusually expressive artistically interesting paintings part of which were pregnant with caricature-like traits, and part with intense colors" (Leuner 1962). In 1952 Lászlo Mátéfi described how an experimental subject under the influence of a hallucinogen experienced a discrepancy between his intention and performance while making a portrait:

After taking 75 µg LSD in a visual psychology experiment in the 1960s, Brooklyn chemistry professor Dr. Gerald Oster (see Figure 6) began an art career dedicated to painting phosphenes with an oil suspension of phosphorescent pigments (Joel 1966; Oster 1970). A 1996 issue of WIRED UK magazine reported that Dr. Mario Markus, of the Max Planck Institute in Dortmund, used Oster's "glow in the dark" paintings to study how hallucinations are produced in the brain:

In 1967 Leonard S. Zegans, M.D. led a research group in the United States that published an LSD creativity study. The creative performance on standardized tests given to 19 LSD subjects was compared to the performance of 11 controls who received a placebo. The researchers concluded that administration of LSD is unlikely to amplify creativity in randomly selected people. However, while acknowledging the limitations of their methodology, the researchers speculated "that greater openness to remote or unique ideas and associations would only be likely to enhance creative thought in those individuals who were meaningfully engaged in some specific interest or problem. There should exist some matrix around which the fluid thought processes can be organized if the experience is not to diffuse into a melange of affective, somatic, and perceptual impressions which may lead to feelings of anxiety or depression" (Zegans et al. 1967).

Frank Barron was first to bring psychedelics to the attention of Timothy Leary by advising him to investigate psilocybin. Barron participated in the early stages of Leary's psilocybin research at Harvard. He published two excerpts from accounts written by artists who were their subjects.

In 1962 in California, Barron and Sterling Bunnell Jr., M.D. organized a series of experiments with several psychedelics, wherein subjects were encouraged to draw, dance, or make music. One of the subjects was psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, who received psilocybin. Several of Naranjo's drawings were published in Scientific American (Barron et al. 1964; Stafford n.d.). While presenting a paper at a creativity conference in 1964, Barron screened film footage of two of his subjects--a dancer and an artist--who were given 30 mg psilocybin. Barron was working at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research at the University of California, Berkeley. Because the institute lacked film equipment, the movie was made by Barron himself, with the assistance of Bunnell. The painter did not want to sketch or paint, but she did want to do photography. The experimenters let her go outside to photograph children and flowers.

In 1964, for the Fifth Utah Creativity Research Conference, Leary published encouraging results achieved by administering psilocybin to 65 artists, musicians, and writers.

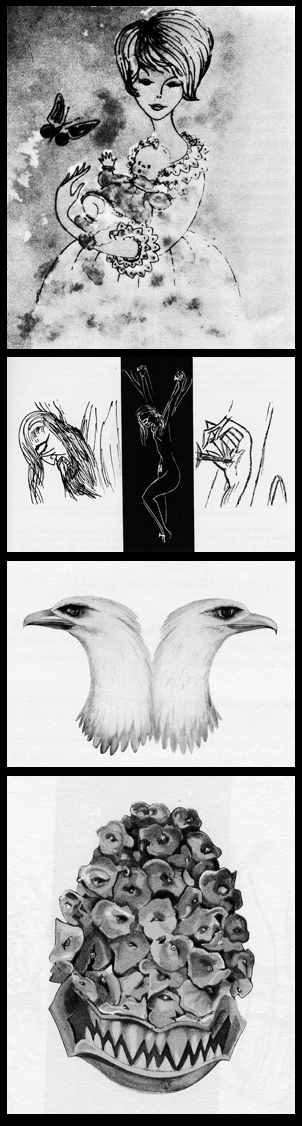

Les Champignons Hallucinogènes du Mexique (Heim & Wasson 1965-1966) contains photographs of ancient mushroom art, such as a picture from an Aztec codex, photographs of mushroom stones and a mycolatrous ceramic figurine, sketches of native use drawn by Conquistador priests, and botanical illustrations--excellent watercolors of different species. Of greater relevance to the student of modern art are the mushroom-inspired images created by French subjects in Paris. One woman painted a watercolor of a smiling mother with child, and ten drawings of human faces and animals. Another subject produced several drawings, one portraying Christ's crucifixion. Another artist created two well-crafted paintings, one of a two-headed bird and another of a many-eyed dragon (see Figure 7).

Sandoz published two collections of art produced by patients undergoing LSD psychotherapy. Psycholytic psychotherapist Hanscarl Leuner (1963, 1974) provided commentary. Sandoz also published psychedelic art in Pandorama Sandoz (March-April 1968) and an issue of Triangle (see Figure 12 at the end of this article). [Erowid Note: The 1961 article "Lysergic Acid and Psychotic Art: When Artists Become Schizoid" in Pfizer Spectrum 9(4): 74-78 is also worth a look.]

In 1979 Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann published pictures of LSD art by both psychiatric patients and normal subjects, in their coffee table book Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use.

Timothy Leary and John Lilly decorated their homes with psychedelic paintings given to them by admirers, but these collections apparently dissipated after their deaths. No substantial collections of psychedelic fine art--either privately owned or in museums--have come to the attention of the public. However, various psychedelic researchers accumulated personal collections of art produced by patients.

Stanislav Grof, M.D., collected art during his practice of LSD psychotherapy in Prague and later at the Spring Grove State Hospital and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. His 1980 textbook LSD Psychotherapy contains 52 black and white plates and 41 color plates (see Figure 9). These pictures included those created by patients undergoing psychedelic therapy, as well as those by Grof himself depicting the types of experiences catalyzed by psychedelics, plus a drawing by Grof of dream imagery from his own therapy while in psychoanalytic training. Further illustrations are found in Grof's other books.

Richard Yensen, M.D., also worked at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. He has a collection that "is from patients in MDA therapy and consists of mandalas drawn at our request with oil pastels" (Yensen 2004).

Betty Eisner collected some paintings produced by her patients during psychedelic therapy. Creating art was part of her treatment protocol from 1957 to 1964 (Eisner 2005).

Salvador Roquet collected art by the patients at his psychedelic psychotherapy clinic in Mexico City from the 1960s through the 1980s. Some of his patients were artists, including Pedro Alatriste, Rodolfo Aguirre Tinoco, and Fred de Keijzer (Clark 1977, cited by Krippner 1980). Dr. Yensen regarded the art by de Keijzer--a Mexican of Dutch ancestry--as particularly notable, and Aguirre Tinoco is still active, having participated in a 2002 group show at Salón de la Plástica Mexicana.

British novelist Aldous Huxley first took mescaline in 1953, under the supervision of Dr. Humphry Osmond. Huxley discussed mescaline and art while delivering the opening address-- "Visionary Experience, Visionary Art, and the Other World"--at the 1954 Duke University Lecture Series in North Carolina (La Barre 1975). Huxley regularly mentioned psychedelics in his lectures at scientific conferences and he informed the general public about them through his talks at universities, magazine interviews, and written works. Nevertheless, in 1960 Huxley expressed a lack of enthusiasm about using psychedelics for art:

In 1955 the French writer Henri Michaux began painting and drawing under the influence of mescaline, apparently without medical supervision. He displayed 22 mescaline ink drawings in 1957 at Gallery One in London (see Figure 11).

|

MESCALINE

Kurt Beringer's 1927 book Der Meskalinrausch presented his study of the effects of injected mescaline hydrochloride on 32 human subjects. Subject #8 was a fine arts painter, but he did not do art during his session. However, some of Beringer's subjects did illustrate their written descriptions of their mescaline experiences. These subjects did not have any artistic training, but their aesthetically unimpressive sketches were the first publication of mescaline's visual imagery uninfluenced by the religious programming of Native American cacti ceremonies.Subjects #3 and #31 were doctors who took 500 mg each, in different experiments. They both drew "trails" produced by the glowing end of a moving cigarette. Subject #31 looked at upholstery with a batik pattern of checks and squares. He then looked at a book, and the textile patterns transferred to the book and proceeded to metamorphose into the designs he represented in three drawings.

Subject #10 was a doctor who was administered 400 mg. He was inside a building looking up at light coming down through a domed concrete ceiling. Closing his eyes, he felt elevated into the dome and identified with it. "It was as if I was inside the cupula, and looking up as the light was going through. At the same time I had a sort of physical sensation of the entire construction, the ability to feel what this kind of iron/concrete construction was like from the inside." The subject drew a grating of iron slates with bronze ornaments that was part of the construction.

Subject #17 was a doctor who was given 400 mg. Looking at a rug, she commented, "The whole carpet seemed to me without sense." She drew a stylized crab, an animated form that she imagined in the carpet.

Subject #18 was a law student who took 400 mg. Either during or after his session, he illustrated the phosphenes that he produced by pressing on his closed eyes. He described, "With closed eyes there was again a strongly ordered surface of color changing like a kaleidoscope and taking on geometrical patterns that were crisscrossing as if lit up by a flashlight."

Subject #23 was a doctor who was administered 500 mg. He drew phosphenes to illustrate the following experience. "I closed my eyes and pressed on the eyeballs and saw small circling white points and later these apparitions transformed into kaleidoscope-like whirls of small red and green flecks of color like an ocean of little pennants. Red and green played from now on until later in the afternoon, and I see only red and green in the world and I am searching for blue and yellow." He also drew "eggdart-molding," which was an architectural molding with filigree ornamentation, that he imagined in the glowing band emanating from an electric lamp that was moving back and forth. The subject was shown a test pattern, designed by the Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer, to test for the perception of illusory movement and colors. The subject recounted: "the pinnacle or apex of the triangle moved from A to B and back. There were no colors, they were gray." The subject drew two sketches of the moving triangle.

"From this black space emerged colorful swastika figures--innumerable, all of them around me, in front and back, above and below, right and left. I must have been in the middle of them. They were not actual swastika, but rather like this (indicating the drawing)."

-- Subject #26

|

In 1932 Frederic Wertham and Manfred Bleuler administered mescaline to normal subjects to study visual hallucinations:

A good impression of these optic phenomena is given by the attempt of one subject to paint in oil a few of the scenes on the day after his mescaline test. He painted four pictures. Since it is very difficult to gain a clear realization of these visual experiences in words, and since mescaline hallucinations are of considerable psychopathological interest, two of these paintings are given here as illustrations (figs. 1 and 2). He wrote of these paintings in his retrospective account:". . . A field of century plants. I have painted only one plane, but there were actually five at the same time. This is the only vision that had any apparent connection with the drug (century plants, pulque, also called mescal). The plants were in sandy fields and did not move in relation to their background, though all five planes moved separately in different directions and at different angles from the eye. (Fig. 1.)

"The second vision was seen while the physician played the phonograph. The background was flames. The black figures moved up black stairways. Their movements were angular and mechanical. In this case there was one background, but the stairs were, like the century plants, at different distances from me. (Fig. 2.)"

|

In 1934 Dr. Fritz Fränkl, who was living in Paris after having fled the Nazis, injected a small dose of mescaline into his roommate, Walter Benjamin (Thompson 1997). Benjamin drew three pictures that consisted of words about sheep and witches poetically scribbled across the page. He also produced, while under the influence of Cannabis, a picture of a bird.

Walter Benjamin is currently an extremely popular philosopher, especially in literary circles. There are fourteen volumes of his work published in German, and five volumes of English translations published by Harvard University Press. One of the foremost experts on Benjamin is George Stiener. In Amsterdam, Stiener opened the 1997 Congress of the International Walter Benjamin Association by giving the keynote address. The assembled congregation of scholars visibly bristled as Stiener lectured about Benjamin's drug usage, which went back at least to 1927, possibly even earlier. Stiener said that the eleven extant drug protocols were only the "tip of the iceberg," because Benjamin had hundreds of sessions with hashish and other drugs. Stiener related these sessions to Benjamin's obsession with Baudelaire and his interest in the influence of dreams and hallucinations on art. Although Stiener emphasized that these experiments occurred before the legal prohibition, when societal attitudes were different than today, the audience was quite disturbed. The academic world fears that mentioning Benjamin's drug use would discredit the legitimacy of his ideas. For example, one contemporary Benjamin scholar--terrified that his career would be ruined if he seemed to encourage drug use--decries any public discussion of Benjamin's pharmacological explorations. Yet he has stated privately that he finds the topic interesting.

"We are very interested in publishing translations of [Walter] Benjamin's work, but we can not undermine Benjamin's reputation by making him appear to be a drug addict."

-- Lindsey Waters,

Executive Editor,

Harvard University Press

Executive Editor,

Harvard University Press

Drs. Eric Guttmann and Walter S. Maclay of Maudsley Hospital studied art produced by psychotic patients and by mescaline subjects. Art generated by their 1936 mescaline experiments is preserved in the Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives and Museum in Kent, England. Bethlem also has a collection of pictures by Richard Dadd and other artists who suffered mental disorders.

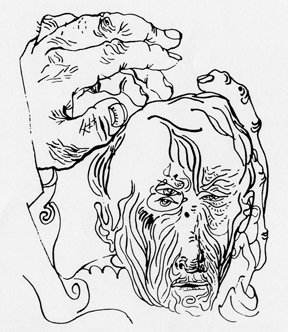

In his 1948 doctoral dissertation for the Medical Facility of the University of Heidelberg, Hans Friedrichs described a series of tests conducted from 1937-1938 at the Psychologischen Institut der Universität Bonn (Psychological Institute of the University of Bonn). The subject of the experiment was a 24-year-old student of philosophy and mathematics who spontaneously produced six drawings approximately eight hours after being injected with 300 mg of mescaline sulfate. These pictures represented the "extraordinary profusion of images powerfully charged, in part, with emotive associations so difficult to describe" that he experienced during the peak of the session. He wrote a statement about the last illustration, which he submitted along with his drawings to the test director:

What I was thinking about as I drew this illustration: Underneath matter, [there is] the Questionable, about which the skeptics argue and are at odds. Chaos, the organic, the imperfect, the inadequate. I am deeply rooted in it, unfortunately. I elevate myself up above it and strive for the realm of pure form, which is the nearest and most immediate passage into the infinite Nothingness. Everything irrational, unworldly is located here, hovering in the Nothingness. Nothingness endlessly encased and concealed inside Nothingness over and over. "God desired to look away from Himself, so He created the world." The sense of this is completely clear to me. The diagonal line [in the illustration] is the limit of time, where space-and-timelessness begin, and into which I can consciously project myself, if I so desire. Here the Will is everything. It alone is capable of giving form to the Nothingness. Everything here is given to it for interpretation: namely Nothing[ness]!

Still remote [is] the Feminine-Maternal, which gave birth to me. Everything else behind me to the right, always in the right, corresponds to it. These unutterably lamentable figures torment themselves over the truth. What is truth? The Nothingness is true. We strive toward it as the one certain thing in death! atastalos! [Greek: ατασθαλος; reckless, presumptuous] (Friedrichs 1948).

LSD

In 1947, Werner Stoll published a small sketch of an LSD-induced "tesselloptic hallucination" in the first article about the psychological effects of LSD.Giuseppe Tonini and C. Montanari worked at the Ospedale Psichiatrico "L. Lolli" in Imola, Italy. In 1955 they administered drugs to an artist who worked in the hospital's occupational therapy department. The two researchers adhered to the psychotomimetic paradigm, and described their subject as a having a normal but "slightly primitive" mind. They asked the artist to paint during his sessions with mescaline, LSD, lysergic acid monoethylamide (LAE 32), as well as with methedrine (both alone and in combination with either mescaline or LSD). He produced paintings during all sessions except the one on LAE-32. The doctors published seven of his paintings of flowers in vases and a landscape, along with a comparison drawing by a schizophrenic. They concluded, "The pictures do not contain any new elements in the creative sense, but reflect psycho-pathological manifestations of the type observed in schizophrenia" (emphasis in the original; Tonini & Montanari 1955). The researchers believed the drawings expressed the differences in the mental states elicited by the different drugs. Although the pictures did look different from each other, it would not have been possible to pick out which picture was painted in an ordinary state of consciousness.

Four prominent American graphic artists were asked by Louis Berlin and his colleagues to paint under the influence of mescaline and LSD. Three subjects were disinclined to paint while peaking, preferring instead to "look and feel," while the remaining subject "painted with great fervor and excitement." Paintings done under the influence of a psychedelic were "works of greater esthetic value appeal according to the panel of fellow artists, but this was associated with a relaxation of control in the execution of lines and employment of color, so that both color and line were freer and bolder." The doctors explained:

This improvement in their esthetic creativity may be explained by the following observations. The subjects became aware of "dead areas and dull colors" in their paintings and were able to modify them. There was a new feeling of unconcern about drawing in a "loose free way", and this loosening of restraint was evident in the size, freedom of line and brilliance of colors employed in their paintings. One artist who described her approach to painting as "indirect and tentative with many changes" felt "relaxed about the mistakes in drawing" and "could cope with them in due time" while under the influence of mescaline (Berlin et al. 1955).

|

Max Rinkle, M.D., initiated the United States' first LSD research in 1949. Rinkle (1955) reported that he and Clemens C. Benda, M.D., "gave mescaline and, on another occasion, LSD to a nationally-known contemporary painter who showed a progressive disintegration in his drawings though each line showed the superior craftsman in his art."

Dr. Jiří Roubíček's 1961 book Experimentální Psychosy (Experimental Psychoses) described research in Prague, providing numerous drawings and paintings, including 20 color plates (see Figures 4 & 5). These pictures were by subjects under the influence of psychedelics (some of whom were well-known professional painters), and by mental patients. Roubíček's book notes that between 1952 and 1960 at the Psychiatric Clinic of Charles University, Czechoslovakian psychiatrists conducted "11 experiments with mescaline on healthy subjects; 130 experiments with LSD on 76 healthy volunteers and 80 experiments on 44 patients; with psilocybin 8 experiments on healthy subjects and 7 on patients; furthermore occasional experiments with other drugs, tryptamine substances and benactizine." The text's English translation summary retains psychotomimetic terminology that characterizes psychedelics as "delirogens" that produce "toxic psychotic conditions." The art of healthy psychedelic subjects is described in comparison to schizophrenic art:

Symbolism is not so much in the foreground and composition is not so profoundly disturbed in the graphic production of volunteer painters in toxic psychotic conditions, especially following the administration of LSD, mescaline and psilocybin. On the whole intoxicated subjects frequently present a spontaneous recording of their hallucinatory and illusionary experiences and often attempt to depict the dynamisms of abruptly alternating visions. In euphoric and hypomanic states their manual speed and available drawing space are sometimes not equal to the flood of dazzling perceptive changes. The expressionistic exaggeration and caricature of some elements in the drawings are reminiscent of the productions from the prehistory of graphic art in which space and time are not yet mastered. Another common feature is the immediacy and directness of the creative product. If a certain regression may be inferred it is one to archetypal levels, to the fundamental features of painting. Such a view is supported by the oft employed ornament during intoxications which is also an ancient mode of expression and is reminiscent of the geometrical records and ornamental drawings in caves and later on various objects of primitive man. In keeping with this view are also the introverted lack of interest in the environment, "spatial insensitivity", loss of established inhibitions and rationally unprepared automatisms. Such regressive mechanisms, however, are in no sense specifically confined to states produced by delirogens; such retrograde processes are repeatedly seen in certain developmental phases of painting. In such comparisons of healthy painters, especially modern ones, we are not concerned here with matters of valuation but with pointers to the understanding of some creative processes.

From all that has been said hitherto it is clear that the symptomatology, electrical brain activity was well as the artistic products of schizophrenics on the one hand and experimentally intoxicated individuals on the other, are so divergent that their differences far outweigh their allied and similar features.

|

I see the object correctly but draw it falsely; my hands won't follow it.... This desire to paint is harder and harder for me to perform since the expanse of my experience pulls me more and more into it. Myself, the drawing, and the surroundings create a unity--and that hinders me because I cannot concentrate on the model. I have the need to bring everything including the painted picture into the surface of the image. Had the painting process been more of a technical success, I would have been able to produce a fantastically good work (Mátéfi 1952).Over the course of seven years, Oscar Janiger, M.D., collected over 250 drawings and paintings by artists who volunteered for his LSD study, which ended in 1962. The artists painted pictures of a kachina doll before and during their LSD session. Part of Janiger's collection was displayed in 1971 at the Lang Art Gallery at Claremont College (Hertel 1971). In 1986 Janiger hosted the exhibit "The Enchanted Loom: LSD and Creativity" at his home in Santa Monica, California. He displayed this art along with commentary by 25 of the artists (Dobkin de Rios & Janiger 2003).

|

To test his hypothesis, Markus investigated sketches made by artist Gerald Oster--sketches he made of the hallucinations he experienced under the influence of LSD. Markus then digitised the images, fed them into his computer, and applied his transformation algorithms to them in order to work out how these visions looked when mapped out according to the topography of the visual cortex. Pleasingly, the spirals and circles were found to correspond to exactly the simple striped Turing patterns that Markus had predicted.In the 1960s the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park and the Institute for Psychedelic Research of San Francisco State College ran a research project on the use of LSD and mescaline for creative problem solving. One of the subjects was a commercial artist. His customer, Stanford University, had rejected several of his presentation sketches for a letterhead. He took a psychedelic for the purpose of developing a saleable design. The university later accepted one of the 26 drawings produced in his session:

I started with modifying the original idea of the presentation sketch a little. After a couple of those I dismissed the original idea entirely, and started to approach the graphic problem radically differently. That's when things began to happen. All kinds of different possibilities began to come to mind, and I started to quickly sketch them out on the blank letter-sized sheets that I had brought with me for that purpose. Each new sketch would suggest other possibilities and new ideas. I began to work fast, almost feverishly, to keep up with the flow of ideas. And the feeling during this profuse production was one of joy and exuberance: I had a ball! It was the pure fun of doing, inventing, creating and playing. There was no fear, no worry, no sense of reputation and competition, no envy; none of these things which in varying degrees have always been present in my work. There was just the joy of doing (Anonymous n.d., in Fadiman, et al. 1965).The artist Arlene Sklar-Weinstein had a single LSD session, which was under the supervision of a psychologist. This experience influenced her paintings for years afterward. She said "it opened thousands of doors for me and dramatically changed the content, intent, and style of my work" (Krippner 1977).

In 1967 Leonard S. Zegans, M.D. led a research group in the United States that published an LSD creativity study. The creative performance on standardized tests given to 19 LSD subjects was compared to the performance of 11 controls who received a placebo. The researchers concluded that administration of LSD is unlikely to amplify creativity in randomly selected people. However, while acknowledging the limitations of their methodology, the researchers speculated "that greater openness to remote or unique ideas and associations would only be likely to enhance creative thought in those individuals who were meaningfully engaged in some specific interest or problem. There should exist some matrix around which the fluid thought processes can be organized if the experience is not to diffuse into a melange of affective, somatic, and perceptual impressions which may lead to feelings of anxiety or depression" (Zegans et al. 1967).

|

PSILOCYBIN

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Sandoz distributed synthetic psilocybin at no cost to European and North American scientists. Consequently, there was a small amount of psilocybin-inspired art before the mid-1970s, when the dissemination of Psilocybe cubensis cultivation methods made "shroom art" accessible to the masses.Frank Barron was first to bring psychedelics to the attention of Timothy Leary by advising him to investigate psilocybin. Barron participated in the early stages of Leary's psilocybin research at Harvard. He published two excerpts from accounts written by artists who were their subjects.

I attempted some drawings but found that my attention span was unusually brief.... Interruptions, such as the model moving, did not really bother me and on at least one occasion a considerable period passed between the beginning of the drawing and its completion (if it could have been called complete even at that point); I simply picked it up and finished it when the occasion presented itself. I seemed to become unusually aware of detail and also unusually unconscious of the relationship of the various parts of the drawing. My concern was with the immediate and what had preceded a particular mark on the page or what was to follow seemed quite irrelevant. When I finished a drawing I tossed it aside with a feeling of totally abandoning it and not really caring very much. In spite of the uniqueness of the experience of drawing while influenced by the drug and my general "what the hell" attitude toward my work I cannot help but feel that the drawings were, in some ways, good ones. I was far better able to isolate the significant and ignore that which, for the moment, seemed insignificant and I was able to become much more intensely involved with the drawing and with the object drawn. I felt as though I were grimacing as I drew. I have seldom known such absolute identification with what I was doing--nor such a lack of concern with it afterward. Throughout the afternoon nothing seemed important beyond what was happening at the moment.The other painter did not comply with the experimenter's repeated encouragement to draw because it seemed to be an invasion of privacy at the time. This subject recounted:

Now I think that the most important part of what has happened to me since the experiment is that I seem to be able to get a good deal more work done. Sunday afternoon I did about six hours work in two hours time. I did not worry about what I was doing--I just did it. Three or four times I wanted a particular color pencil or a triangle and would go directly to it, lift up three or four pieces of paper and pull it out. Never thought of where it was--just knew I wanted it and picked it up. This of course amazed me but I just relied on it--found things immediately. My wife was a little annoyed at me on Sunday afternoon because I was so happy, but I would not be dissuaded.It is now understood that artists will be most productive if they approach their session with an emotional commitment to a specific project; particularly for naïve subjects, they should be already working as their consciousness begins to alter.

When painting it generally takes me an hour and a half to two hours to really get into the painting and three or four hours to really hit a peak. Tuesday I hit a peak in less than half an hour. The esthetic experience was more intense than I have experienced before-- so much so that several times I had to leave the studio and finally decided that I was unable to cope with it and left for good! I now have this under control to some extent but I am delighted that I can just jump into it without the long build-up and I certainly hope it continues (Barron 1963).

In 1962 in California, Barron and Sterling Bunnell Jr., M.D. organized a series of experiments with several psychedelics, wherein subjects were encouraged to draw, dance, or make music. One of the subjects was psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, who received psilocybin. Several of Naranjo's drawings were published in Scientific American (Barron et al. 1964; Stafford n.d.). While presenting a paper at a creativity conference in 1964, Barron screened film footage of two of his subjects--a dancer and an artist--who were given 30 mg psilocybin. Barron was working at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research at the University of California, Berkeley. Because the institute lacked film equipment, the movie was made by Barron himself, with the assistance of Bunnell. The painter did not want to sketch or paint, but she did want to do photography. The experimenters let her go outside to photograph children and flowers.

In 1964, for the Fifth Utah Creativity Research Conference, Leary published encouraging results achieved by administering psilocybin to 65 artists, musicians, and writers.

Les Champignons Hallucinogènes du Mexique (Heim & Wasson 1965-1966) contains photographs of ancient mushroom art, such as a picture from an Aztec codex, photographs of mushroom stones and a mycolatrous ceramic figurine, sketches of native use drawn by Conquistador priests, and botanical illustrations--excellent watercolors of different species. Of greater relevance to the student of modern art are the mushroom-inspired images created by French subjects in Paris. One woman painted a watercolor of a smiling mother with child, and ten drawings of human faces and animals. Another subject produced several drawings, one portraying Christ's crucifixion. Another artist created two well-crafted paintings, one of a two-headed bird and another of a many-eyed dragon (see Figure 7).

CANNABINOIDS

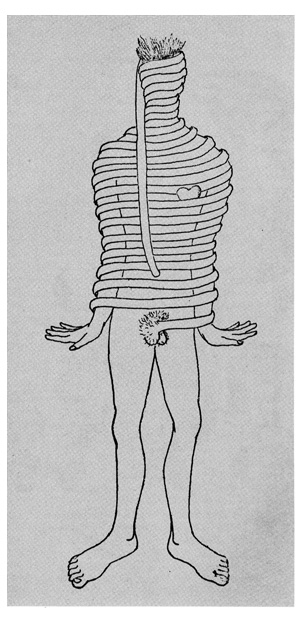

In his book detailing psychedelic experiments conducted by the U.S. Army at the Edgewood Arsenal, Dr. James Ketchum published four pictures by an experimental subject who was administered EA 2233 in late 1961. EA 2233 was a mixture of eight stereoisomers of THC with a heptyl (seven-carbon) side chain that had been invented by chemist Harry Pars. Ketchum explained, "At intervals during the experiment subjects were required to "Draw-a-Man", a commonly used projective test, indicating distortion of self image as well as the physical and mental capacity to create a coherent representation of the human body" (Ketchum 2006).

|

MANDALAS AND THERAPY

The term "mandala" originally referred to Vajrayana Buddhist icons that resemble Hindu yantras. In 1969, Joan Kellogg began having her psychotherapy patients use oil pastels to make circular paintings, which she called "mandalas." Kellogg collaborated with Helen Bonny, the pioneering music therapist who worked at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center (see Figure 8). From there, mandalas were popularized in New Age circles by Stanislav Grof's Holotropic Breathwork. In 1977 Kellogg published two pictures of mandalas drawn by an alcoholic who underwent therapy with an unspecified psychedelic at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. The patient drew a series of seven mandalas over the course of his treatment. A full description of the case was provided in the unpublished manuscript The Use of Mandalas in a Case of Psychedelic-Assisted, Time-Limited Psychotherapy.CREATIVITY RESEARCH ENDS

The last scientific experiment on psychedelic art was at the Max Planck Institute in Munich (Krippner 1985, citing Kipphoff 1969). In the late 1960s Richard P. Hartmann administered LSD to numerous well-known artists, devoting about one week to each subject (Hartmann 1974). Artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser refused to paint while under the influence of LSD. Gerd Hoehman could not paint due to a headache elicited by remembering a wartime experience. The work of C.O. Goetz was indistinguishable from his ordinary paintings. Alfred Hrdlicka, usually a technical perfectionist, drew caricatures and primitive shapes with crude gusto. Waldemar Grzimek attempted to draw a female figure but developed anatomy problems insoluble with his charcoal pencil. The paintings by Heinz Trokes demonstrated an almost complete disappearance of form. Eberhard Eggers and Thomas Häfner succeeded in transferring their mental images onto canvas, and Eggers' canvas was judged to show improved artistry. Part of the experiment was televised, demonstrating a change in the artists' behavior. Werner Schroib, reputed to usually have an aggressive manner, chatted pleasantly while drawing. Manfred Garstka had a nightmarish time, commenting "I held fast to painting for it was the only thing I had to cling to to save myself from total submergence in an inferno." All the artists concurred that the experience was of value and the work was placed on display in a Frankfurt gallery. German web sites carry more information about this experiment, including a description in a dissertation, testimonials by some of the artists, a photograph of an artist painting under the influence of LSD, and more recent psychedelic art by one artist who participated in the Kunstrausch (Inebriation Art) show in Hamburg.EXHIBITS AND COLLECTIONS

In Mexico City in 1971 there was a large exhibit of dozens of paintings and drawings produced by psychiatric patients under the influence of LSD and other hallucinogens. Most of the art came from Eastern Europe where psychedelic psychotherapy was still allowed. Little or none was from the United States, as by then therapists were prohibited from administering psychedelics to patients. This exhibit was displayed at the Museum of Anthropology in connection with the Fifth World Congress of Psychiatry. The Congress, which in various years had presentations on psychedelic psychotherapy, convened at a conference center near the museum.

|

In 1979 Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann published pictures of LSD art by both psychiatric patients and normal subjects, in their coffee table book Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use.

|

Stanislav Grof, M.D., collected art during his practice of LSD psychotherapy in Prague and later at the Spring Grove State Hospital and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. His 1980 textbook LSD Psychotherapy contains 52 black and white plates and 41 color plates (see Figure 9). These pictures included those created by patients undergoing psychedelic therapy, as well as those by Grof himself depicting the types of experiences catalyzed by psychedelics, plus a drawing by Grof of dream imagery from his own therapy while in psychoanalytic training. Further illustrations are found in Grof's other books.

Richard Yensen, M.D., also worked at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. He has a collection that "is from patients in MDA therapy and consists of mandalas drawn at our request with oil pastels" (Yensen 2004).

Betty Eisner collected some paintings produced by her patients during psychedelic therapy. Creating art was part of her treatment protocol from 1957 to 1964 (Eisner 2005).

Salvador Roquet collected art by the patients at his psychedelic psychotherapy clinic in Mexico City from the 1960s through the 1980s. Some of his patients were artists, including Pedro Alatriste, Rodolfo Aguirre Tinoco, and Fred de Keijzer (Clark 1977, cited by Krippner 1980). Dr. Yensen regarded the art by de Keijzer--a Mexican of Dutch ancestry--as particularly notable, and Aguirre Tinoco is still active, having participated in a 2002 group show at Salón de la Plástica Mexicana.

POP CULTURE

News about art produced in experiments gradually diffused to the general public. In 1953 Newsweek published an article about the use of mescaline in psychiatry entitled "Mescal madness." This featured surrealist composite photographs by German photographer Leif Geiges that simulated "the mental patterns described by mescal users."British novelist Aldous Huxley first took mescaline in 1953, under the supervision of Dr. Humphry Osmond. Huxley discussed mescaline and art while delivering the opening address-- "Visionary Experience, Visionary Art, and the Other World"--at the 1954 Duke University Lecture Series in North Carolina (La Barre 1975). Huxley regularly mentioned psychedelics in his lectures at scientific conferences and he informed the general public about them through his talks at universities, magazine interviews, and written works. Nevertheless, in 1960 Huxley expressed a lack of enthusiasm about using psychedelics for art:

|

Some experiments have been made to see what painters can do under the influence of the drug, but most of the examples I have seen are very uninteresting. You could never hope to reproduce to the full extent the quite incredible intensity of color that you get under the influence of the drug. Most of the things I have seen are just rather tiresome bits of expressionism, which correspond hardly at all, I would think, to the actual experience. Maybe an immensely gifted artist--someone like Odilon Redon (who probably saw the world like this all the time anyhow)--maybe such a man could profit by the lysergic acid experience, could use his visions as models, could reproduce on canvas the external world as it is transfigured by the drug.The pulp magazine Fate published sensationalistic articles about pseudoscience, parapsychology, and the occult. "Magic Land of Mescaline," the lead story for a 1956 issue of Fate, was an account by Claude Chamberlain, an experimental subject who took mescaline under medical supervision in a laboratory. Despite making numerous erroneous statements, the author astutely suggested that mescaline might provide a "shortcut" to achievement for artists, inventors, philosophers, and theologians. As cover art for this article, Lloyd N. Rognan produced a color painting of a beautiful blond woman--clad only in a flowing diaphanous scarf--prancing through a strange landscape with a polychromatic explosion in the sky (see Figure 10). This picture also appeared in the story itself, along with a drawing of a man who was hallucinating a voluptuous nude woman orbiting the planet Saturn. These pictures did not correspond to the text, and there is no indication that the artist had ever ingested a psychedelic himself; he was probably just assigned the task of conveying the impression that mescaline grants instant access to cosmic marvels and libidinal titillation.

|

FUTURE TRENDS

In 1962 underground LSD distribution began in the United States. Consequently, psychedelic art rapidly developed outside of clinical experiments and merged with Cannabis-inspired art. Since the early 20th century, some indigenous hallucinogen-using artists have employed modern painting materials and European artistic conventions such as shading and perspective, and distribution to an international market. In the 1990s, non-native artists began experiencing visionary plants in traditional shamanic settings. Contemporary psychedelic art and indigenous hallucinogen-inspired art will undoubtedly continue to converge in the 21st century.

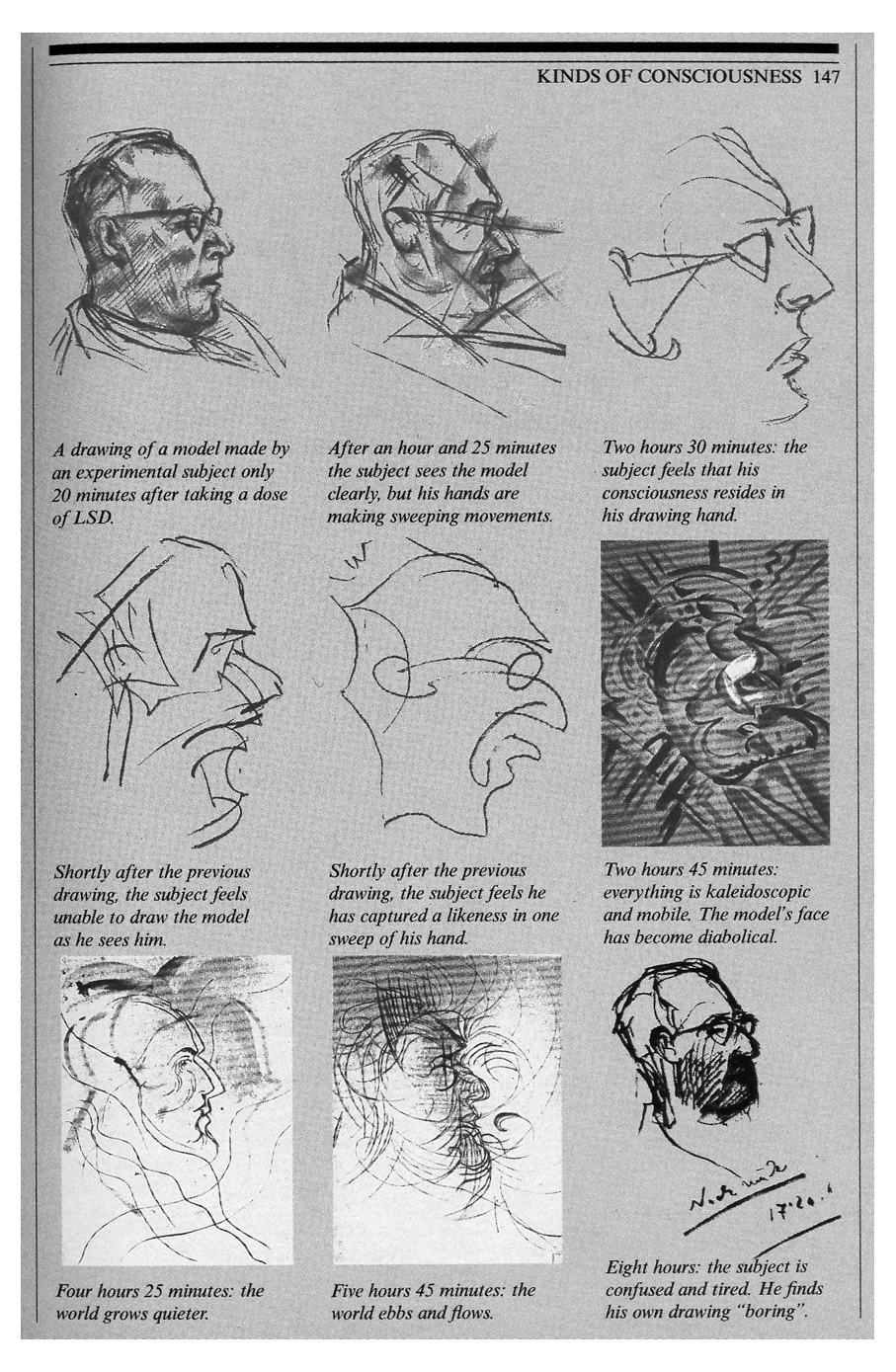

FIGURE 13. Assorted drawings of a model made at various stages of LSD inebriation (Lászlo Mátefi). |

References #

- Anonymous n.d., in Fadiman, J. et al. 1965. Use of Psychedelic Agents to Facilitate Creative Problem Solving: Creativity Project Progress Report #1. The Institute for Psychedelic Research of San Francisco State College. p. C-1.

- Barron, F. 1963. Creativity and Psychological Health: Origins of Personal Vitality and Creative Freedom. D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. pp. 74, 251, 253-254.

- Barron, F. 1964. "The Relationship of Ego Diffusion to Creative Perception," Widening Horizons in Creativity: The Proceedings of the Fifth Utah Creativity Research Conference. Calvin W. Taylor (ed.). John Wiley & Son, Inc. pp. 80-86.

- Barron, F. et al. (April) 1964. "The Hallucinogenic Drugs," Scientific American 120(4): 29-37.

- Beringer, K. 1927. Der Meskalinrausch: Seine Geschichte und Erscheinungsweise. Verlag von Julius Springer. pp. 42, 147, 181, 208, 216, 246, 248, 251, 267-269, 299-300, 303.

- Berlin, L. et al. 1955. "Studies in Human Cerebral Function: The Effects of Mescaline and Lysergic Acid on Cerebral Processes Pertinent to Creative Activity," Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 122: 487-491.

- Boon, M. 2002. The Road to Excess: A History of Writers on Drugs. Harvard University Press. pp. 218-275.

- Chamberlain, C.W. 1956 (January). "Magic Land of Mescalin," Fate 9(1): 14-21. Issue 70. Clark Publishing Company.

- Clark, W.H. 1977. "Art and Psychotherapy in Mexico," Art Psychotherapy 4: 41-44.

- Dobkin de Rios, M. & O. Janiger 2003. LSD, Spirituality, and the Creative Process. Park Street Press. pp. 25-26, 83, 113.

- Eisner, B. 2005. "Betty Eisner: The Birth and Death of Psychedelic Therapy," in Higher Wisdom: Eminent Elders Explore the Continuing Impact of Psychedelics. R. Walsh & C. Grob (eds.). SUNY Press.

- Figuier, L. 1868. Les Merveilles de la Science, ou Description Populaire des Inventions Modernes (Tome II): Télegraphie Aérienne, Électrique et Sous-Marine Cable Transatlantique -- Galvanoplastie -- Dorure et Argenture Électro-Chimiques -- Aérostats -- Éthérisation. p 665.

- Friedrich, H. 1948. Zeichnerische Illustrationen zum Meskalinrausch. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg.

- Grof, S. 1980. LSD Psychotherapy. Hunter House, Inc.

- Guttmann, E. & W.S. Maclay 1936. "Mescaline Experiments. Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives and Museum." Transcripts: BHM 698v; BHM 44; BHM.

- Guttmann, E. & W.S. Maclay 1937. "Clinical Observations of Schizophrenic Drawings," British Journal of Medical Psychology XVI (parts 3 & 4): 184-205.

- Hartmann, R.P. 1974. "Malerei aus Bereichen des Unbewussten: Künstler experimentieren unter LSD," Kšln. M. DuMont Schauberg.

- Heim, R. & P. Thévenard 1965-1966. "Expériences Nouvelles d'Ingestion des Psilocybes Hallucinogènes," Chapter V, pp. 201-211 in: Heim, R. & R.G. Wasson. 1965-1966. Les Champignons Hallucinogènes du Mexique: Études Ethnologiques, Taxinomiques, Biologiques, Physiologiques et Chimiques. 7th series, Volume IX. Archives du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Éditions du Muséum. Also see the first part: Volume VI (1958).

- Hertel, C. 1971. Portrait of the Artist with Two Heads: A Study of Stylistic Changes Influenced by the Ingestion of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Scripps College Art Galleries.

- Huxley, A. 1960 (spring). "The Art of Fiction XXIV," The Paris Review 23: 57-80.

- Jakimowicz, I. 1985. Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz: Witkacy Malarz. Wydawnictwa Artystyczne I Filmowe. pp. 66-70. plates XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, pp. 139-145, 147, 168-169, 173, 182.

- Joel, Y. 1966 (September 9). "Psychedelic Art," Life 61(11): 60-69.

- Kellogg, J. et al. 1977 (July). "The Use of the Mandala in Psychological Evaluation and Treatment," American Journal of Art Therapy 16: 123-134.

- Ketchum, J.S. 2006. Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten: A Personal Story of Medical Testing of Army Volunteers with Incapacitating Chemical Agents During the Cold War (1955-1975). ChemBooks Inc. pp. 38-41.

- Kipphoff, P. 1969. "Artists and LSD," Encounter 35: 34-36.

- Knauer, A & W.J.M.A. Maloney 1913. "A Preliminary Note on the Psychic Action of Mescalin, with Special Reference to the Mechanism of Visual Hallucinations," Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 40: 425-436.

- Krippner, S. 1977. Research in Creativity and Psychedelic Drugs, International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis XXV (4): 274-290.

- Krippner, S. 1980. "Psychedelic Drugs and the Creative Process," The Humanistic Psychology Institute Review 2(2): 9-34.

- Krippner, S. 1985. "Psychedelic Drugs and Creativity," Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 17(4): 235-245.

- La Barre, W. 1975. The Peyote Cult, 4th edition. Archon Books. pp. 206, 209.

- Leary, T. 1964. "The Effects of Test Score Feedback on Creative Performance and of Drugs on Creative Experience," pp. 87-111 in Widening Horizons in Creativity: The Proceedings of the Fifth Utah Creativity Research Conference. C. W. Taylor (ed.). John Wiley & Son, Inc.

- Leuner, H. 1962. Die Experimentelle Psychose: Ihre Psychopharmakologie, Phänomenologie und Dynamik in Beziehung zur Person: Versuch einer konditional-genetischen und funktionalen Psychopathologie der Psychose, Springer-Verlag. p. 51.

- Leuner, H. 1963. "Die optische Halluzinose und ihre Sinngehalte," Psychopathologie und Bildnerischer Ausdruck vol. 3. Sandoz.

- Leuner, H. 1974. "Masques et Faces Grimaçantes dans l'Hallucinose Toxique," Coll. Psychopathologie de l'Expression vol. 21. Sandoz.

- Maclay, W.S. & E. Guttmann 1941 ( January). "Mescaline Hallucinations in Artists," Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 45(1): 130-137.

- Marinesco, G. 1933. Presse Médicale 74: 1433.

- Mátéfi, L. 1952. "Mescalin- und Lysergsäurediäthylmamide-Rausch Zeichentests," Confinia Neurologica 12: 146.

- McKellar, P. 1957. Imagination and Thinking: A Psychological Analysis. Basic Books, Inc. Publishers.

- Newsweek 1953 (February 23). "Mescal Madness," Newsweek : 92-94.

- Oster, G. 1970 (February). "Phosphenes," Scientific American : 82-87.

- Rinkle, M. 1955. "Summary of Papers on Drugs Affecting Behavior," Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 122: 487-491.

- Roubíček, J. 1961. Experimentální Psychosy. Státní Zdravotnické Nakladatelství. pp. 257-258.

- Saurí, J.J. & A.C. de Onorato 1955. "Las Esquizofrenias y la Dietilamida del ácido d-lisérgico (LSD 25) I. Variaciones del Estado de ánimo," Acta Neuropsiquiátr Argent 1: 469.

- Schultes, R.E. & A. Hofmann 1979. Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 176-183.

- Stafford, P. n.d. Magic Grams: Inquiries into Psychedelic Consciousness. Self-published. pp. 58-59.

- Stiener, G. 2002. Benjamin Studies I: Perception and Experience in Modernity. Rodopi. p. 17.

- Stoll, W.A. 1947. "Lysergsaurediathylamid, ein Phantastikum aus der Mutterkorngruppe," Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiat 60: 279-323.

- Szuman, S. 1930. "Analiza formalna i psychologiczna widzeń meskalinowych," Kwartalnika Psychologicznego 1.

- Thompson, S.J. (1997). "Protocol XI: Fritz Fränkel: Protocol of the Mescaline Experiment of 22 May 1934," Protocols to the Experiments on Hashish, Opium and Mescaline 1927-1934: Translation and Commentary. [Posted at www.wbenjamin.org/protocol1.html#XI, accessed Jun 13, 2013.]

- Tonini, G. & C. Montanari 1955. "Effects of Experimentally-Induced Psychoses on Artistic Expression," Confinia Neurologica 15(4): 225-239. [Available at Erowid.org/references/refs_view.php?ID=4021.]

- Wertham, F. & M. Bleuler 1932. "Inconstancy of the Formal Structure of the Personality: Experimental Study of the Influence of Mescaline on the Rorschach Test," Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 27: 52-70.

- WIRED UK. 1996 (February 2). "The Mind's Inner Eye's Inner Mind,". WIRED UK 2. [Posted at www.jbf.dial.pipex.com/art_tech_ec_files/markus.htm, accessed Jun 13, 2013.]

- Witkiewicz, S.I. 1992 (translation of 1932 essay). "Narcotics: Nicotine, Alcohol, Cocaine, Peyote, Morphine, Ether," in The Witkiewicz Reader. D. Gerould (ed.). Northwestern University Press. p. 264.

- Yensen, R. 2004 (January). Personal communication.

- Zegans, L.S. et al. 1967 (June). "The Effects of LSD-25 on Creativity and Tolerance to Regression," Archives of General Psychiatry 16: 740-749.

Revision History #