1957 - 2010

A Tribute to Glauco Vilas Boas

Beloved Brazilian cartoonist and a leader in the Santo Daime religion, slain in São Paulo1

v1.1 - Aug 20, 2010

Citation: Labate BC, Alves Jr. AM, de Rose IS, Lemos JA. "A Tribute to Glauco Vilas Boas: Beloved Brazilian cartoonist and a leader in the Santo Daime religion, slain in São Paulo". Erowid.org. May 6, 2010: Erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca_info14.shtml

"Glauco was a great chronicler of Brazilian society, he understood the habits and customs of our people and expressed it with intelligence and humour. The news of his death made me sad and I was shocked by the horrible circumstances which also left his son Raoni a victim. It was a tremendous loss. In the face of this real tragedy, I would like to express my condolences to his relatives, friends and fans."

-- Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, president of Brazil4

Introduction

On the night of March 12, 2010 Glauco Vilas Boas and his son, Raoni Vilas Boas, were shot to death at their house in Osasco in São Paulo (SP). Glauco was one of Brazil's best-known cartoonists and leader of the Céu de Maria church in SP, one of the largest Santo Daime centers outside of the Amazon region, while his son was a young university student. The person charged with the murders is 24 year-old Carlos Eduardo Sundfeld Nunes ("Cadu"), a 24 year-old member of an upper-middle class family in São Paulo (SP). Allegedly suffering from problems of drug abuse, a schizophrenic mother and an inability to work or study for several years, he had joined the Santo Daime religious rituals directed by Glauco in search of relief and healing.The tragic death of Glauco and his son has made the debate about ayahuasca a national issue in Brazil, where the use of this controversial substance, which has sporadically caught the attention of the media for the past 25 years, has been legal since the mid-eighties. At first, with very few exceptions, the media covering the murders showed a respectful attitude towards Santo Daime. Even when the controversies surrounding the case began to emerge their approach to the religion itself remained neutral. However, this suddenly changed when, after being captured when trying to escape to Paraguay, the alleged murderer told TV reporters that he wanted to kidnap Glauco to prove to his family that he was Jesus Christ (and thus avoid being forcibly placed in a psychiatric clinic by his family). Other than that, his father and lawyer claimed that Cadu had gone "psycho" after joining the Santo Daime rituals, which caused a sudden shift in the media towards the stereotyped, anti-drugs point of view usually found in their coverage of the use of psychoactive substances. Many reports of the case in newspapers, magazines, TV programs and internet sites uncritically set forth the theory that the consumption of ayahuasca had been responsible for the crime, as seen, for example, in the covers of two of the Brazil's most popular weekly magazines, Veja and Época.

Up to what point is it justifiable to allow the use of an hallucinogenic drug in the rituals of a sect? |

The death of the cartoonist Glauco reopens the debate about the use of the indigenous drug ayahuasca in religious rituals.5 |

The story of Glauco's death is full of paradoxes. The artist who made gentle fun of Brazil's political and economic problems was violently murdered; the religious leader who generously supported people in search of help was killed by an ex-member of his church. For us, as investigators and defenders of the use of psychoactive substances in general and of the Brazilian ayahuasca culture in particular, his departure is perplexing and raises many questions. Nevertheless, it is not our intention here to engage in a sociological discussion of them. For one thing, this would involve dealing with subjects which have been largely ignored by the media coverage of his death, such as the trafficking of drugs and arms in Brazil, urban violence, the lack of alternative treatments of drug abuse in the public health system and the problematic treatment of psychiatric diseases in general. For another, the fact that Cadu had drug problems and probably sought out Daime as a mean of treating his addiction leads us to the important discussion of ayahuasca's potential benefits for the treatment of drug abuse, or its potential harm when consumed in conjunction with other legal or illegal substances and/or by people with specific psychiatric conditions. These matters lead, in turn, to questions about the borders between the "religious" and "therapeutic" uses of ayahausca -- while the first is allowed in Brazil, the second is not. In the neighbouring country of Peru ayahuasca, on the contrary, is associated with the traditional medicine of indigenous peoples and uses of it defined as "therapeutic" are legal.

Thus this essay is mainly meant to challenge the media's mainstream approach to the death of Glauco. It is composed of three parts. In the first we provide an account of Glauco's spiritual development, presenting a facet of his life of which the general public was largely unaware. In the second we present some of tributes to Glauco by his fellow cartoonists in Brazil, and provide translations and commentaries that will give foreign readers a clearer idea of the characters he created and the nature of his humour. The homage paid to him by his colleagues, who, following the spirit of Glauco's personality and humour, make fun of his death is beautiful and touching, and also represents an interesting source material for the art-critical analysis of cartoons, insofar as they provide insights into the relationship between art, representation and reality: the characters he created, who inhabited our imagination as real beings, now suffer and die as well. In the last part, we briefly present a few of Glauco's cartoons related to the world of Santo Daime. One of them, Miraldinho, remains largely unknown, as it was published exclusively in a small tabloid of a Daime community, which lasted only a few issues. The other two, Mestre Alfa and Cacique Jaraguá, on the other hand, were published in Brazil's major newspaper - but their sources of inspiration in the Santo Daime universe also remain almost a secret. These cartoons offer a rare and fascinating intersection of Glauco the artist and Glauco the Santo Daime devotee.

The other side of Glauco: Religious leader of Santo Daime

Born in 1957, Glauco published his first works in the newspaper Diário da Manhã of Ribeirão Preto (São Paulo state) at the end of 1970s and it was in that period that he won several prizes for his cartoons. At the beginning of the 1980s, he began to publish in the Ilustrada supplement of the Folha de São Paulo, Brazil's best selling daily newspaper, with a circulation of over 300,000. Among his unforgettable characters there were Geraldão, who first appeared in 1981, after the cartoonist read Carlos Castañeda; Casal Neuras; Doy Jorge; Dona Marta; and Zé do Apocalipse. In the 1980s he was the editor of the magazine Geraldão and contributor to the magazines Chiclete com Banana and Circo. He also formed part of the creative team of the television program TV Pirata and played a part in the creation of some features of the children's program TV Colosso, both from the Rede Globo network. His name was always associated with the cartoonists Angeli and Laerte (also well-known in Brazil) because of their similar outlooks on life and the fact that they worked for the same newspaper for 25 years. With his acid humour, quick wit and fluid pen strokes, Glauco played an important part in the modernization of graphics and the style of Brazilian cartoons in a period marked by the advent of the post-dictatorship generation. His work dealt with daily subjects such as marital problems, neuroses, loneliness and urban violence, always with humour. It would be difficult to find anyone among us Brazilians who was not inspired, at one time or another, by the lively comic-strip characters that Glauco created.It would have been even more difficult for most admirers of the cartoonist to imagine that another person lived behind that irreverence, the priest of a large Santo Daime community who welcomed followers and visitors from every corner of São Paulo, other Brazilian states and even foreign countries. It is unfortunate that it was only through a violent tragedy that Brazil came to know the inner side of that charismatic man who influenced a whole generation of youngsters and artists.

Glauco first became familiar with Santo Daime in a house on the Cardeal Arcoverde street, a meeting place for a small group who came to form the original nucleus of Flor das Águas, the first Daime church in São Paulo, founded in 1988, in São Lourenço da Serra, which no longer exists. (We should recall that the first Daime churches established outside of the Amazon region were Céu do Mar, in Rio de Janeiro; Céu da Montanha, in Mauá and Céu do Planalto, in Brasília, all founded in the early 1980s).

After participating in Flor das Águas, Glauco began to hold his own ceremonies in 1993 in a small shack at the bottom of the garden of his house in Butantã, the start of the small Daime Church of Céu de Maria. The group later moved to the outskirts of the city, in the Jaraguá mountain region. Perhaps to his own surprise, this church slowly turned into one of the biggest centers of this religious movement outside of the Amazon jungle.

Thus, it might be said that Céu de Maria is an expression of the intense expansion Santo Daime went through after its tentative exit from the Amazon region at the end of the 1970s and its gradual establishment in the big cities of Brazil and the world. For many city dwellers, his church has been a gateway to the enchanted world of Santo Daime and its pantheon of divine beings. There is no doubt that Céu de Maria was the main center of the religion in the city of São Paulo.

Glauco himself was a witness to the profound personal transformations Daime can effect -- a drink referred to as the "Master Teacher" or the "Teacher of teachers", given to mankind by the Queen of the Forest (Rainha da Floresta). These transformations were what motivated him, through the spiritual practices of Daime, to furnish a whole generation of men and women with the possibility of entering into contact with the spiritual dimension of existence. A talented musician, he played the accordion during the rituals and "received" (by divine inspiration, in accordance with the Daime tradition) two "hinários" (collections of "hinos", hymns), "Chaveirinho" ("The Little Key-Ring") and "Chaveirão" ("The Big Key-Ring") respectively made up of 42 and 11 hymns each. His best known hymn is number 19 of the "Chaveirinho" collection emblematically entitled "São Paulo", one of whose verses says: "I am going to receive this force... the force of my Lord... to found with my Saint Paul... a house of love" (Eu vou receber esta força... a força do meu Senhor... para fundar com meu São Paulo... uma casa de amor.) The church, a refuge of greenery in the midst of the city, has an unequalled landscape. Perhaps in no other part of São Paulo is it possible to enjoy such a panoramic view of the city. From there the traveller can see, from high above, the whole chaotic, frenzied and amorphous shape of São Paulo -- against a background of Daime chants in ceremonies that can last up to fifteen hours.

Glauco led these "works" with great humility, refusing to assume the title of "padrinho" (godfather), one of the honorifics for the spiritual leaders of Santo Daime, and speaking little; sooner or later he'd make a joke or a play on words, using his outstanding talent for humour and joy as a way to teach his followers. His home alongside the church served as a kind of embassy for the Amazon in the megalopolis and was always full of people. He ran the church with the help of his family, among them Raoni, a student of multimedia, who was also played the guitar during the ceremonies and hoped to become a guitar-maker. Céu de Maria, under the command of Glauco and his team, was known for the beauty of its songs and instrumentation. It is worth recalling, in accordance with our studies, that music plays a central role in Santo Daime, which is also known as the "musical doctrine".

His deep-rooted Christian faith, which was joined to the shamanic practices of the "caboclos" (mestizo jungle dwellers), is well illustrated by an incident which took place when Céu de Maria was founded. When he moved to the house in Butantã which also housed the earliest rituals of his new church, he met up with a small group of street kids who were squatting there. Instead of kicking them out, he initiated them into his rituals, saving some from the streets. Now adults, some of those are still followers of Santo Daime.

That kind of courage and faith made a strong impression on large groups of urban, middle class people who were attracted to his church. And, as inevitably happens in any church, Céu de Maria also exerted its pull on the afflicted, in search of spiritual redemption. The sorrow evident in the large crowd that attended Glauco's funeral is a testimony to the deep love which he awakened in others and an acknowledgement of the positive role he represented for everyone. Even though this Daime "Céu" (Heaven) on earth will certainly go on without the presence of Glauco, we are going to miss him a great deal. Sad as it is, this tragic event should not be an obstacle to the full flourishing of the Daime culture in our country. It is just the opposite: his life story should serve as an inspiration for future generations.

The cartoonists' tributes to Glauco6

Glauco's main character, Geraldão, a man of 30 who complained he was "still a virgin", always walked around with his addictions: multiple bottles, cups, cigarettes, syringes and hot dogs. Here he appears in heaven, asking: "Where are my thirty virgins?", "...And the refrigerator"? |

The creatures with the creator. The three surfing E.T.s are high above, and below, from the left: Dona Marta (a sex-starved secretary), Netão (an internet addict), Doy Jorge (with the green skin), the Neuras Couple together with their little green Monster of Jealousy, Apocalypse Joe, Geraldão and Nojinsk (an eccentric and always silent Arab). Geraldinho, the child version of Geraldão, clings to the wall. |

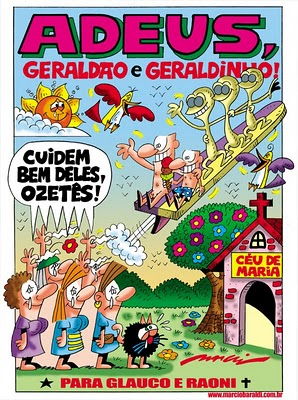

Under the heading "Goodbye, Geraldão and Geraldinho!", Glauco's characters cry out: "Take good care of them, E.T.s!", in front of Glauco's SantoDaime church, Céu de Maria. |

This character, Zé do Apocalipse ("Apocalypse Joe"), was constantly preaching the end of the world. Here he holds a sign which says "The End" and, in the background, in red: "Peace" |

Apocalypse Joe holds a torn Brazilian flag broken (Glauco also did a lot of political cartoons) |

The characters he created say goodbye to him. "Glauco, wherever you are... A big hug from Bira" (the cartoonist's name) |

Dressed in the white suit of Santo Daime, Glauco plays the accordion, as he always did during their rituals. |

Geraldão and his mother hold on to Glauco, while he flies up to the sky. |

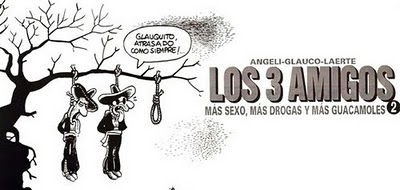

The characters called Três Amigos (Three Friends) showed Glauco and his friends and fellow cartoonists Angeli and Laerte in the guise of Mexican bandits. Here the latter two drop their guns before Glauco, with the word "Peace" above them. Underneath, the names of Glauco and his son Raoni. |

"Yahoo! New flavour!" says Geraldão in Heaven... "Good bye Glauco!" |

Another group of characters created by Glauco, "Ozetês" (The E.T.s.), who hang out in the Cosmos, either meditating or surfing in search of psychoactive mushrooms and beautiful women from other parts of the Universe: "Don't be sad... The guy is up here with us... We'll see each other one day...", they say. |

"The End has come!", says "Apocalypse Joe" by Glauco's grave. |

"Upload Glauco... No, no, I made a mistake... Shit... Now it is already done!" |

Geraldão gets to heaven, and says: "No shit! That talk about angels not having sex is serious!". On the side, the cartoonist writes "Rest in peace, master!" with his signature below. |

"Sniff, sniff! Why did you leave so early?" cries out Glauco's fan. "Sorry, folks! But the situation in Brazil is really hard... I had to do some overtime!", answers the Reaper. |

First comes Geraldão. Then, three more of Glauco's characters, Casal Neuras ("The Neurotic Couple", a hilarious case of pathological jealousy) and Doy Jorge, a drug addict. So, the word "sniff" means both crying and snorting cocaine. |

Geraldão, his mother... and flatulence, another constant element in Glauco's jokes. The artist signs "Rafael Rosa, in homage to Glauco, impossible to equal." |

"Oh yes! Miguelitos! ("Little Michael" in Spanish)", exclaims Glauco, dressed as one of The Three Friends. In their comic strip, the Miguelitos were the goody-goody little boys the bandits loved to terrorize. |

"Two more beloved sons... Glauco and Raoni rest in peace", says this cartoonist. The Brazilian flag, with its "Order and Progress" motto, is pierced by a syringe, of the kind Geraldão used. |

"We're getting there, Sharon Stone!!!", Geraldão says to his blonde inflatable doll near a sign saying 'Heaven' (He also had a brunette doll called Sônia Braga, the name of a famous Brazilian actress and sex symbol). |

"Glauquito, late as always...", cries out Angeli, with Laerte, another one of The Three Friends, hanging by his side. "More Sex, More Drugs and More Guacamoles" says the phrase under the title of the comic strip. |

"Thou shalt not kill", writes Geraldão. |

Geraldão's ghost appears by the bedside of Brazilian president Lula. "We'll keep scaring them for you! Go with God, Glauquito" ("Little Glauco" in Spanish, as he was often called.) |

Glauco's few cartoons related to Santo Daime #

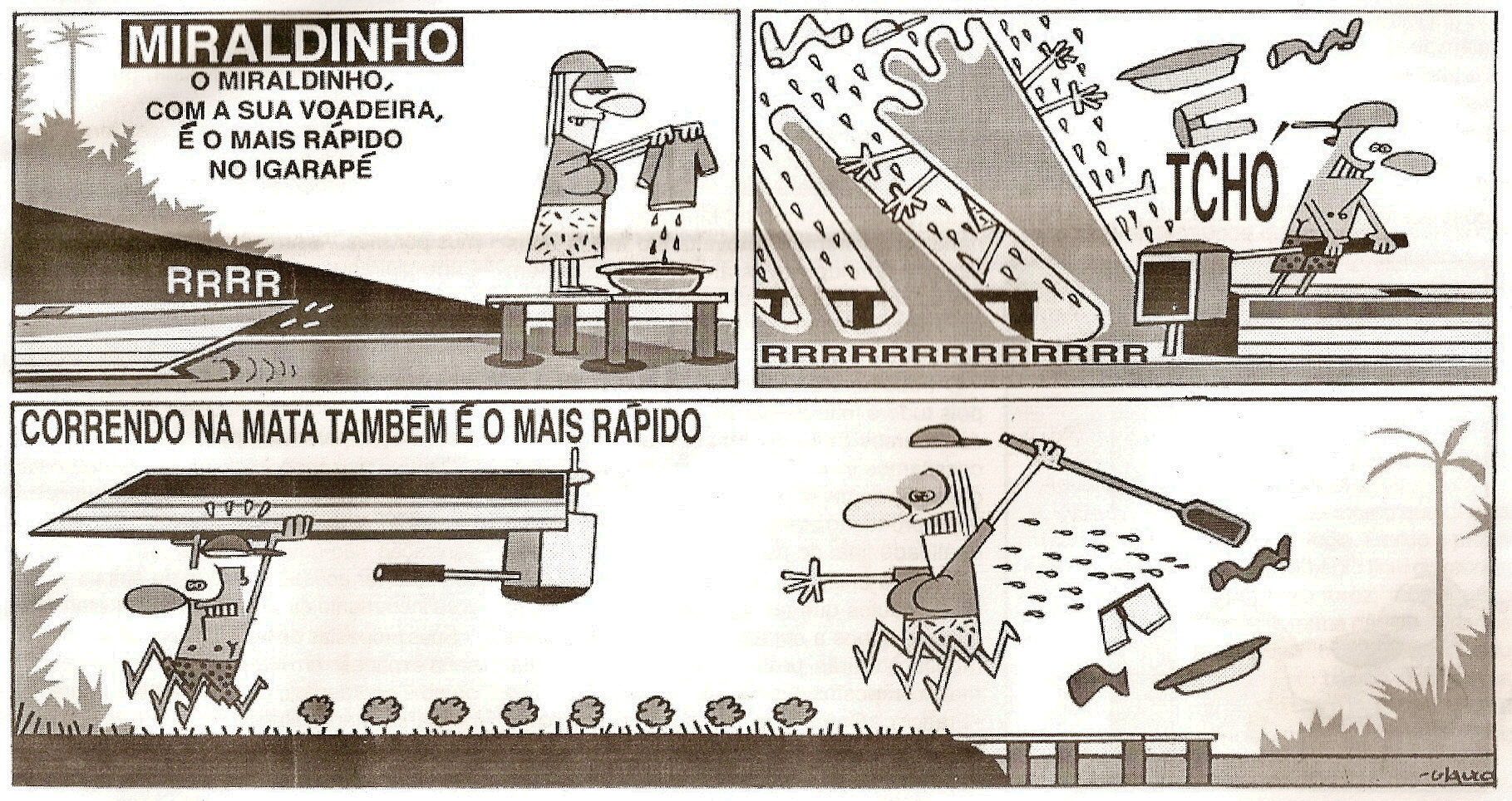

Here we present one cartoon where the character "Miraldinho" appears. "Miraldinho" was specifically created by Glauco for a community newspaper, briefly published at Céu do Mapiá, Santo Daime's headquarters in the Amazon, to which Glauco's church was affiliated. Glauco had already created Geraldinho ("Little Gerald", a typical big city kid, addicted to TV, soda pop, hotdogs and ice creams) as a juvenile version of his main character, Geraldão ("Big Gerald") -- so Miraldinho can be seen as a Santo Daime version of Geraldinho. His name is a play on the word "miração", which, while seldom heard in Brazil, is commonly used in the Brazilian ayahuasca churches Santo Daime, UDV and Barquinha. In broad terms, it means "to be under the effect of ayahuasca" and its more specific meaning is "to have an ayahuasca vision". This character did not have a long life or defined personality; he only appeared a few times. In this comic strip Miraldinho is at an "igarapé", a small jungle stream typical of the region in and around Céu do Mapiá . One usually reaches the community by river and there, as in other Amazon villages, the river is also the place where the local people wash dishes and clothes, bathe and have social gatherings, etc.

|

In a short-lived series, Master Alfa used to appear strolling about the Amazon rainforest as counterpoint to the main character called Zé Malária ("Malaria Joe"), an anthropologist from the big city in the more developed southeast of Brazil who ventures into the jungle desperately afraid of dangers such as venomous animals, with his potent insecticide spray can in hand.

© Folhapress |

My crown has arrivedSome time later, almost certainly inspired by the spiritual entity announced in his hymn, in a most peculiar case of cross-fertilization between a solemn religious-spiritual manifestation and pop culture, Glauco turned the caboclo Cacique Jaraguá into his last cartoon character, Cacique Jaraguá. This is an old Indian chief who suffers from deep nostalgia for the times when the urban landscape had not obliterated his virgin forest, telling tall tales of his hunting prowess and other skills to his little grandson.

The one I was waiting for

Who sent it was my Master

And the Sovereign Queen

The Master's crown landed

On the Jaguar's head

Who was here taking care

Is Currupipipiraguá

Receive my crown

For I will graduate you

Reminding you of the caboclo

Old Chief Jaraguá

It is worth noticing that Jaraguá ("Lord of the Valley" in the indigenous Tupi language) is the name of the mountain close to Céu de Maria (Pico do Jaraguá, [Jaraguá Peak]), which dominates all the surrounding scenery, above the sprawling city skyline. In Cacique Jaraguá's comic strips, Glauco always made puns with the names of São Paulo's districts and neighborhoods, turning them into different tribes -- with a kind of humor that people who are not familiar with the city will probably find hard to understand.

© Folhapress |

Notes #

- This text is a modified and expanded version of the Portuguese original one compiled by: Labate, Beatriz C.; Alves Jr, Antonio M. & Rose, Isabel S. "A outra face de Glauco Vilas Boas, líder religioso do Santo Daime. Folha Online. 21 March 2010. Available at: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/folha/cotidiano/ult95u709924.shtml

- Beatriz Caiuby Labate is an anthropologist, member of the research staff at the Institute of Medical Psychology at Heidelberg University and researcher at the Interdisciplinary Group for Psychoactive Studies (Núcleo de Estudos Interdisciplinares sobre Psicoativos -- NEIP, www.neip.info); Antonio Marques Alves Jr. obtained a Masters degree in religious studies at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica of São Paulo (PUC-SP), is a Researcher of NEIP and the leader of the Reino do Sol Santo Daime church in Paralheiros (São Paulo); Isabel Santana de Rose is Ph.D. Candidate in Social Anthropology at the Universidade Federal of Santa Catarina (UFSC) and a researcher at NEIP; José Augusto Lemos is a journalist and member of the Santo Daime church.

- Jimmy Weiskopf is a journalist, translator, author of a book on the use of yajé (ayahuasca) in Colombia, and an informal follower of Santo Daime.

- Correio Braziliense, March 12, 2010. Available at http://www.correiobraziliense.com.br/app/noticia182/2010/03/12/brasil,i=179277/

- For an analysis of these two pieces, see: Labate, Beatriz C. "A lamentável reportagem da Revista Veja sobre a morte de Glauco". São Paulo, Casa Amarela, 01/04/2010. Available at: http://carosamigos.terra.com.br and Labate, Beatriz C. "Caso Glauco - Cobertura com muitos equívocos". Observatório da Imprensa, ano 14, nº 583, 30 de março de 2010. Available at: http://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/artigos.asp?cod=583JDB005

- Source: http://universohq.blogspot.com

- Jornal do Céu (Heaven's Newspaper), Céu do Mapiá, Year 2, No. 4, June 1998.

- Videotaped musical performance of Coroa available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Wi1EoEOSLM.

Image Credits #

Revision History #